The Building Blocks:

The history of ideas about the economy, from theories to methods, from mainstream and heterodox economics to other disciplines studying the economy.

What

This building block lays out the history of ideas about the economy. This includes the history of economics as a discipline, both mainstream and heterodox, as well as how other disciplines have analysed the economy over time. It also covers the different methods used throughout the history of the discipline. Since intellectual developments never take place in a vacuum, we suggest coupling this history of ideas with the historical contexts in which they evolved as described in Building Block 3: Economic History.

Why

History of thought about the economy is a crucial element in the training of future economists, for two reasons. First, it helps to structure and understand current ideas. It enables students to organise and group the various insights they gain, by giving them an overview of their shared roots. This helps students to develop a more direct or personal relationship to economic ideas and theories, as well as prominent (economic) thinkers. Second, it shows that the current paradigm is not the only way to think about the economy and that ideas about the economy change over time. This encourages critical thinking and provides students with fresh insights from a broad set of ideas, old and new.

Contrast with current programmes

Generally, economic programmes today hardly include any history of economic thought, and where they do, we propose a broader history of economic thought than is usually taught. The scope we suggest is the history of ideas around the economy, rather than the history of how today’s mainstream academic discipline (economics) came to be. That includes ideas from both orthodox and heterodox economics, as well as from other social science sub-disciplines such as economic sociology, economic anthropology and economic geography.

“We cannot help living in history. We can only fail to be aware of it.”

Robert Heilbroner (1960, p. 209)

Throughout most of his study programme, one of the authors of this book experienced economic theory largely as an unstructured cloud of individual models, papers, names and methods. He perfectly well understood each of these on its own, and was well aware that they all dealt with similar types of subject matter. But he found it difficult to see how it all connected to each other.

It was only when he followed a (relatively short) online course in history of economic thought, that this amorphous mass of ideas and techniques began to take a defined shape. Central principles emerged. Ideas began to group themselves. As the fog lifted, a clear structure became visible: all those unconnected models and names turned out to be the many branches of a few large trees, connected at the base in their common roots.

In our view, this is the main purpose of teaching history of economic thought: to give students an overview of the larger structure, a coat rack upon which to hang the ideas presented throughout the programme. It is also an excellent opportunity to include critical thinking, as different perspectives can be compared and contrasted.

The purpose of a course on economic history is not to teach ‘forgotten theories’. If they were unjustly forgotten, we suggest teaching them in theory and topic courses based on their contemporary value, not as historical relics. Nor is it to show how history inexorably leads up to the current set of mainstream ideas, as the best incarnation of economic thinking to date.

If anything, we propose a history of economic thought that shows how ideas clash, how schools of thought compete and how the winner is not always the most useful or insightful one. Politics, power, personalities and pure luck play a large role in this, as any good historian of economic thought will make abundantly clear.

We thus simply propose to expose students to this diverse and complex history, rather than trying to present some simple linear story of progress which leaves out many crucial and fascinating parts of the history. In this way, a history of economic thought can help students to understand what lies behind different economic ideas and debates, enabling them to make their own judgments as economists.

Such a genealogy of ideas is useful for all students, a structure in which they can house the various individual tools gained throughout the programme. But there is one group for whom it is especially valuable: those going into research roles themselves. An economist who only reads current publications and is ignorant of the economic ideas developed before them, is awkwardly at risk to spend enormous amounts of time and energy to reinvent the wheel. In addition, they are far more likely to lack crucial critical thinking skills. Understanding the ideas and their contexts will on the other hand give students a broader perspective of economic ideas and allow them to see it in a more holistic manner. This is crucial in the making of future economists, where they are better equipped to make judgement of current economic ideas and debates. A financial employer of UK economists argued economics programmes should start with the history of economic thought as the great economists of the past “have a large amount to tell us about how economies are run” (Yurko, 2018, p. 11).

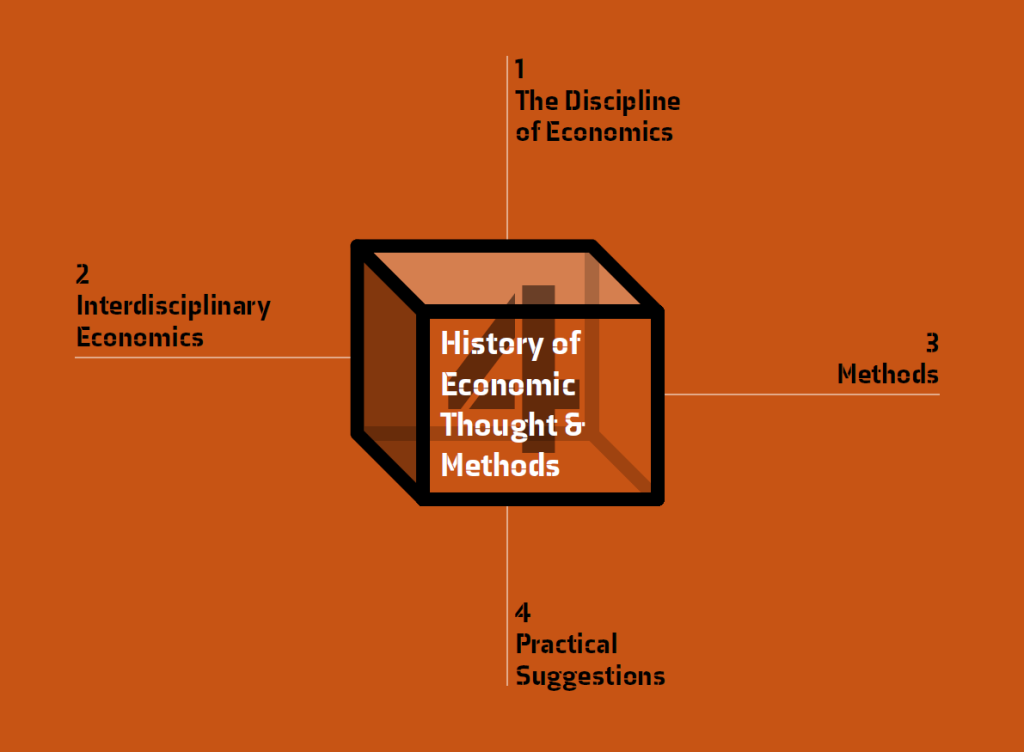

For conceptual convenience, we divide the historical material into three different sections in this chapter. We start with the discipline of economics. The next section highlights several valuable ways of studying the economy, which currently have a home in other social disciplines. The third section deals with the history of methods. However, we do not necessarily advocate using these categories to organise a course. They are simply heuristic devices. In the last section of the building block, we do discuss various ways to structure courses.

1. The Discipline of Economics

When teaching students about the history of the discipline of economics, it is important to expose students to the diversity by which it is characterised. We will emphasise two different expressions of diversity here: diversity in terms of people and diversity in terms of ideas.

Firstly, it is important to recognise the diversity in terms of people in the history of economic thought. Since most societies were, and still are, dominated by white males, it is perhaps no surprise that the same applies to economics. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the many relevant contributions of female and non-white thinkers are not ignored. In terms of including schools of thought, for this reason it seems particularly important to include approaches such as feminist and structuralist economics. But the point goes beyond this. There have been many important contributions from female and non-white thinkers in almost every approach. Thus, we need to actively include a larger diversity of thinkers into curricula, and go beyond the old, limited, set of white male economists.

This already starts at the roots of the discipline: do we teach Adam Smith (1776) as the founder of the discipline, or Ibn Khaldun (1377), who outlined early theories of division of labour, taxes, scarcity, economic growth, and the origins and causes of poverty? Subsequently we find that histories are currently often presented as exclusively male. This is not quite accurate. Ursula Webb Hicks and Vera Smith Lutz, for example, made highly influential contributions to neoclassical economics throughout the twentieth century, in particular with regards to the role of banking in economic development (Brillant, 2018). There are also important more recent thinkers, male and female, from the Global North and Global South, such as Jayati Ghosh and Thandika Mkandawire, who are critical of the neoclassical approach to economic development, international economics and macroeconomic policy. It is imperative that we include such examples in the story of economic thinking that we tell students.

Besides discovering the diversity of voices, students should become familiar with the diversity of economic theory. We suggest not to focus exclusively on one school of thought or the mainstream of the discipline, but rather to showcase debates between different points of view and include discussions of dissent thinkers as well as the dominant paradigms at points in time. As such, it does not suffice to tell the typical story, starting from the classical political economists, moving to the birth of neoclassical economics, the Keynesian revolution and finally to the formation of the modern discipline after the second world war. While each of these episodes are important in the history of the discipline, this story leaves out many crucial elements.

Students would, for example, miss the fact that the historical school, in particular its German branch, was highly influential during the 19th century. Not only in terms of theoretical and empirical work, but also in terms of influencing actual policies of countries; by placing the state at the centre of its analysis. This strand of thought, in turn, was crucial for the emergence of institutional economics in the United States. This approach also significantly contributed to the theoretical, empirical and policy work that economists engage in. These are just two examples. It would also ignore the long history of Marxian and Austrian economic thought, and more recent history of structuralist, ecological, behavioural, evolutionary, feminist and complexity economics.

A course cannot practically cover every approach in detail; rather, the goal should be to make clear to students that there exist many different and sometimes conflicting ways of thinking about the economy. It is crucial to explicitly discuss these debates and intellectual conflicts that have shaped the history of the discipline. This helps students get a sharp understanding of how approaches differ from each other, place theoretical ideas into perspective and think independently.

One way to do this would be to examine a limited number of intellectual conflicts in a bit more detail. This can help students understand how economic debates work, from the construction of arguments to the importance of institutional power. For example, one could discuss the so-called Cambridge Capital Controversy (Cohen & Harcourt, 2003). This was a debate in the 1950’s and 1960’s between the post-Keynesian economists such as Nicholas Kaldor, Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge (UK) and the neoclassical economists such as Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow and Franco Modigliani at MIT (US Cambridge, Massachusetts) on whether it makes sense to define capital, as an input of production processes, by its monetary price. Though technical, the debate had far-reaching consequences. For one, the post-Keynesian economists argued that the neoclassical mathematical models of economic growth were internally inconsistent. Although this was admitted to indeed be the case by leading neoclassical economists such as Paul Samuelson, those models did remain in use as they defended them based on their practical usefulness.

Descriptions of such historical skirmishes provide students a view behind the curtain of the discipline, showing how even the most widespread ideas can be fruitfully questioned. To be sure, the point here is not to choose sides when discussing these debates. Students should be given a fair presentation of the different sides of the debates and they should make up their own mind as to which arguments they find more convincing. Learning how to make these kinds of judgments is a key skill economists need to learn that they will require for their future work, so we should help and trigger students to do so, rather than just trying to convince them of one point of view.

2. Interdisciplinary Economics

Economists are not the only ones who have thought about the economy. Many valuable insights into how economic processes work have been developed by other social scientists. If we would solely focus on the ideas of economists, we would thus miss out on important insights. Therefore, it is key that courses on the history of economic thought also include ideas on the economy developed in other disciplines.

There are a number of fields that are of particular importance here: economic sociology, economic geography, economic history, economic anthropology and political economy. These are all sub-disciplines that (typically) exist outside the field of economics but are nevertheless organised around studying the economy. As such, they form important traditions and fields in the history of economic thought and should be taught as such.

One way to include these neighbouring disciplines is again by examining a single concept from different perspectives. For example, the meaning of money and value (creation) is one of the economic discipline’s main concepts but perceived very differently in the various other fields that study it. Disciplines such as anthropology and sociology, for example, contributed a lot to our understanding of money and value, paying particular attention to social networks, culture and power relations (Carruthers & Ariovich, 2010; Graeber, 2005; Hart, 2005).

Another concept to explore from the perspective of different disciplines is the market. For instance, economic sociologists using a cultural approach have found that market devices, which refer to cognitive tools, technologies and rules of thumb, fundamentally alter economic outcomes, such as prices, rather than only facilitating economic life to be more efficient (MacKenzie et al., 2007). By taking a different approach to the economy, new insights are generated.

A key part of the literature on these market devices focuses on the ideas and mathematical models of economists, which turn out to be crucial market devices that shape economic processes. A good example is how the Black-Scholes-Merton model shaped how derivatives traders priced options (MacKenzie, 2008; MacKenzie & Millo, 2003). While in the beginning the model was fairly weak at empirically describing or predicting how option markets behaved, slowly more and more traders began to use the model. In doing so, it created its own reality as it strongly began to structure option markets and as a result became fairly good at predicting market behaviour for a while. And as such, the market device performed, rather than simply described, economic life. Thus, this literature also illustrates the performativity of economics: the study of economics does not simply (try to) reflect the world, but influences and performs upon the world it studies through its methodology.

If the history of economic thought is confined to the ideas of economists, students would not experience these alternative perspectives nor grasp as easily the performativity of economics. Therefore, we advise to include interdisciplinary insights into how economies work in courses on the history of economic thought.

3. Methods

Finally, methods are a crucial aspect of the history of human beings and their understandings of economies. Economic thought is strongly shaped by the methodological tools used to study the economy and, as such, methods are a key aspect of teaching history of economic thought.

Just as with the history of theories, the history of methods is both diverse and complex. Therefore, again, instead of focussing on the technical details, students should acquire a rough understanding of how different methodological approaches developed, evolved over time and in particular conflicted. Exposing students to these debates helps them to think critically about methodological choices made in literature as well as their own.

Students should learn about how the different methods evolved over time and shaped economic thought as a result. A key part of this history is how statistics slowly developed as the economists’ method of choice during the 19th and early 20th century. Throughout this period, many different forms of statistical analysis developed and competed with each other as well as other methods, such as interviews and qualitative historical analysis. After the Second World War in particular, a strongly mathematical approach to economics became more and more dominant, and still today skills in mathematics are seen as crucial for success. Students have much to gain by learning about this complicated and fascinating history.

There have been many other clashes of methodological views that one could discuss with students. For example, the Methodenstreit during the late 19th century between Austrian economists, such as Carl Menger, who argued for using deductive reasoning, and German economists favouring historical and comparative statistical approaches. Alternatively, there have been many debates about how to best study business cycles throughout the twentieth century between economists such as Wesley Clair Mitchell, Jan Tinbergen, John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman and Lawrence Klein. And many recent discussions have been about the use of experimentation and simulation in economics (Maas, 2014).

4. Practical Suggestions

Given the large scope of history, we first advise to focus on particular examples and be selective in terms of geographic or temporal scope. Second we discuss organising the content effectively depending on your goal: either by theoretical approach or chronologically, and in a standalone course or lectures that are part of a broader course. And finally, we consider the need to include the contexts in which ideas developed.

Firstly, it is important to realise that one can never be completely comprehensive. No course will have enough teaching time to discuss all relevant economic thinkers in history. So, how then to focus and select ideas and thinkers to teach? As stated in the introduction of this chapter, we think the history of economic thought can be very useful to help students organise their thinking and be able to place specific ideas in a larger intellectual tree of economic thought. As such, it is important to allow students to develop an understanding of the different branches of this tree. We would therefore advise to make students familiar with the various branches, without necessarily going into great detail into all of them. Next to giving such a broad overview of the history, one could go into more detail into specific debates and ideas to also give students more concrete knowledge and a feeling of the history, rather than studying it as if history was a concatenation of isolated events. Independently of this, one could focus on the history of thought in the country the university is located in. The history of economic thought is often dominated by the UK and US; however, for a programme situated in Brazil, for example, it makes sense to pay particular attention to how economic thinking has evolved there. In general, we should make the history of economic thought less Eurocentric; for instance, why should we teach about Adam Smith as ‘the father of economics’ while ignoring many others, such as Chanakya and Ibn Khaldun, who wrote about the same topics centuries earlier?

Secondly, there are a number of ways in which courses can be structured. A course can be entirely dedicated to the history of economic thought, but the topic can also be a small part of a broader course (Dow, 2009). In a course on micro or financial economics one could, for example, devote one lecture to the history of the ideas that will be discussed in more detail throughout the course. When teaching a course on the history of economic thought one could organise it by theoretical approaches. One would thus discuss the history of Marxian political economy, followed by the history of neoclassical economics, followed by the history of complexity economics, etc. Another way to organise such a course is to structure it chronologically: first discussing the early history of dispersed individual economic thinkers, subsequently the formation of the discipline and ending with its recent developments.

Thirdly, it can be very helpful to take time to discuss the contexts in which ideas emerged: history of economic thought can be fruitfully combined with economic history as well as broader social, cultural and political history. For instance, Adam Smith’s notion of the division of labour becomes a more insightful story when coupled with his visit to a proto-factory for pins, one of many small firms arising in that age of early industrialisation. It becomes even more interesting when we add a description of the general economic circumstances of the time; the growing class of landless peasants looking for paid jobs following the enclosures of their commons, and in the background a growing tide of political liberalism.

An interesting teaching technique might be to let students assume the positions of various historical thinkers or schools of thought, and then debate from those positions, in written or spoken form. This can help students practice understanding others and placing themselves in others’ shoes, which stimulates active reflection on the topic. Besides teaching them the mental flexibility of understanding and taking on various positions, this also helps to develop their faculties of writing and public speaking.

In addition, students can learn a lot from reading (parts of) original texts, whether it is The Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels (1848), the Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren of Keynes (1930), The Use of Knowledge in Society by Hayek (1945), Equality of What? by Sen (1979), How Did Economists Get It So Wrong? by Krugman (2009) or Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems by Ostrom (2010). This gives students a direct impression of economic debates and helps them understand and reflect upon them. Reading classics is, however, a time intensive task, so it is important not to assign too much text. How much is too much, of course, depends on the teaching level and available teaching time. Our advice is to let students read (small) parts of original texts accompanied with secondary literature and teaching materials on the ideas and history. Besides reading old texts, it can also be insightful for students to watch or listen to old debates and presentations. The two classic television series The Age of Uncertainty by John Kenneth Galbraith, originally broadcasted in 1977, and Free to Choose by Milton Friedman, originally broadcasted in 1980, for example, give an informative view on the economic debates of the time.

Teaching Materials

- The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times and Ideas of the Great Economic Thinkers by Robert Heilbroner, most recent edition from 1999. While first published in 1953, it remains perhaps the best introduction into the history of economic thought to this day. In a remarkably well-written and accessible manner it discusses the ideas of key economists and puts them into historical context.

- Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius by Sylvia Naser, from 2012. Another very accessible but more recent book introducing the history of economic thought through captivating narratives.

- Economic Methodology: A Historical Introduction by Harro Maas, from 2014. A well-written and useful book on the history of economic methodology from debates about deduction and induction, statistics, modelling, and experiments in economics.

- The History of Economic Thought Website made by INET: http://www. hetwebsite.net/het/. A useful collection of material and discussions of different schools of thought, historical periods and institutions.

- A Companion to the History of Economic Thought by Warren J. Samuels, Jeff E. Biddle, and John B. Davis, from 2003. An extensive and detailed collection of contributions covering many periods and developments in the history of economic thought, as well as covering historiography and different ways of approaching that history.

- Routledge Handbook of the History of Women’s Economic Thought by Kirsten Madden and Robert W. Dimand, from 2019. A unique history of economic thought book focusing on the too often ignored contributions of women around the world.

If one is looking for more standardised textbooks, these three other options might be useful.

- History of Economic Thought by David Colander and Harry Landreth, from 2001, is accessible and transparently opinionated, triggering students to think for themselves and form their own opinion.

- History of Economic Thought by E. K. Hunt and Mark Lautzenheiser, most recent edition from 2015, is written from an explicitly critical perspective on the current mainstream profession and reflects upon great thinkers of the past, how today’s dominant approach developed and approaches that have been pursued at the margins of the discipline.

- A History of Economic Theory & Method by Robert B. Ekelund and Robert F. Hébert, most recent edition from 2016, is the most extensive of the three and covers the classics as well as more innovative topics such as economics’ relation to art, religion, archaeology, technology and ideology.

- As with economic history, national history is always particularly relevant. The Routledge History of Economic Thought book series can be useful for this, as it contains books on many countries, such as A History of Indian Economic Thought by Ajit K. Dasgupta from 2015, The History of Swedish Economic Thought by Bo Sandelin, most recent edition from 2012, and Studies in the History of Latin American Economic Thought by Oreste Popescu, from 2014.