The Building Blocks:

A pragmatic pluralist approach to theory, focusing on the most important insights for every topic.

What

This building block provides a map through the complex jungle of economic theories. There are many schools of thought and each aspect of the economy has been analysed by a number of different schools. However, it is neither feasible nor productive for students to engage with every possible angle for every topic. Hence, this building block sets out an alternative approach: pragmatic pluralism. That is, make a selection of the most relevant theoretical approaches for the topic that is taught. Furthermore, before going into specific theories, teach students about the core assumptions that approaches make.

Why

Teaching theory in social sciences is important because it allows one to understand the components, processes and causal mechanisms characterising various social phenomena in a more structured and systematic manner. However, every topic can be understood from various theoretical perspectives, which can complement or contradict each other. It is essential to teach students a variety of approaches in order to give them a rich and broad understanding of the topic as well as the debate around it. This also helps them learn how to think critically and not take things as absolute truths.

Contrast with current programmes

Most contemporary economics programmes focus almost exclusively on neoclassical theory. In opposition to this, some argue to focus entirely on another perspective. We believe, in contrast to both, that there is no single ‘correct’ or ‘best’ way to understand the economy as a whole. It is too large and complex to be captured by a single point of view. Hence, we propose a fundamentally pluralist approach to teaching theory. Approaches should be judged on their merits, topic by topic: thinking critically and reflectively to decide which theoretical points of departure help us best to understand this particular corner of the economic system.

“Scientific knowledge is as much an understanding of the diversity of situations for which a theory or its models are relevant as an understanding of its limits.”

Elinor Ostrom (1990, p. 24)

The goal of teaching economic theory is to familiarise students with the most relevant ideas about how economies work. Given that there are many such important insights, what should students be taught in the short time available for a course? What will help them most to understand the economic world around them? One answer to this question is to follow a standard economics textbook. Polished, well-structured and widely recognised, it is no wonder most teachers choose this option. Unfortunately, most textbooks available today cover only the relatively narrow theoretical space of neoclassical economics. While this school of thought has much to offer, using solely a neoclassical textbook means students miss out on all other economic insights, and do not learn to compare different ideas and choose the one most valuable for the question at hand.

There are many reasons for making programmes more pluralist. First, no single theoretical framework explains everything: theories complement each other in many ways and are thus required to obtain a more complete understanding of the economy. Second, there are conflicting points of view and debates about virtually any economic topic. A pluralist education helps students to realise that they always have a choice as to how to approach issues, that there is no single ‘right’ answer nor one ‘correct’ method that is always superior. An education that leaves out such discussion, does not prepare students for the real world in which there is also often debate about what is the right way to understand an issue. Third, a pluralist programme introduces students to a wider range of economic wisdom collected throughout the past centuries, much of which regains its relevance time and again. These and other reasons for choosing theoretical pluralism are set out in more detail in Foundation 2: Pluralism, earlier in this book. In that chapter, we also discuss several of the most frequent objections to theoretical pluralism.

In practical terms pluralism might not look attractive at first sight. If we teach a plurality of theories, where does it stop? It would be impossible to cover all of the theoretical approaches when teaching on a concrete topic, such as the financial system. ‘Indiscriminate’ pluralism is impossible in practice.

In this building block we therefore present a more pragmatic way to teach theory in a pluralist way, focusing on the most important insights for every topic. Among all our building blocks, this one has by far the most content to discuss. For this reason, it is the largest of our ten building blocks and has a more complex internal structure.

This building block is structured as follows. In the first section, we discuss the need to introduce the main assumptions underlying different economic perspectives, before presenting their specific insights and more sophisticated theoretical work. Next we discuss interdisciplinary economics, which reveals that many key economic ideas and research do not stem from academic economists. In the third section we set out the general pragmatic pluralist approach: focus on the theoretical perspectives that seem most relevant in the specific thematic area one teaches about. The final section provides practical suggestions on teaching economic theory in a pragmatic pluralist way.

1. Introducing Economic Perspectives

Before delving into the specific insights that economic perspectives provide, it is important that students become familiar with their basic assumptions. What assumptions are made about what the economy is made up of, how it changes and how human beings act? What methodological preferences and normative ideas are typical? Without such basic knowledge, it is likely that students will perceive theory classes as one big blur with endless random insights. Armed with a basic understanding of what differentiates perspectives, students are able to situate and contextualise the insights that the perspectives have on specific topics. In other words, it allows them to see the bigger picture and connect the dots.

To keep such an introduction manageable, we suggest focusing on the core intuitions of perspectives, rather than presenting students with fully fleshed out models or mathematical representations. Furthermore, the core perspectives in the programme can be selected so that not too many perspectives are included within a single course. When introducing perspectives, the history of an approach can be of great use: it provides context and a broader understanding of its contribution to economic thinking.

The theoretical perspectives that we cover in this book are:

- Austrian School

- Behavioural Economics

- Classical Political Economy

- Complexity Economics

- Cultural Approach

- Ecological Economics

- Evolutionary Economics

- Feminist Economics

- Field Theory

- Historical School

- Institutional Economics

- Marxian Political Economy

- Neoclassical Economics

- Post-Keynesian Economics

- Social Network Analysis

- Structuralist Economics

For each of these approaches, we start with the key assumptions and aspects, followed by a brief history of the approach and some suggested low-threshold teaching materials to introduce students to the approach. There is no space in this book for sixteen such overviews, but to demonstrate what can be found on our website, we have included two examples below. The first is neoclassical economics and the second post-Keynesian economics.

Neoclassical Economics

Key assumptions and aspects:

- Main concern: Efficient allocation of scarce resources that maximises consumer welfare

- Economies are made up of: Individuals

- Human beings are: (Hyper)rational, self-interested and atomistic individuals with fixed and given preferences, also called ‘homo economicus’ and ‘economic man’

- Economies change through: Individuals optimising decisions

- Favoured methods: Equilibrium models and econometrics

- Typical policy recommendations: Free market or government intervention, depending on assessment of market and government failures

Neoclassical economics arose out of the marginalist revolution, during the long depression which started in the 1870s. Neoclassical economics was largely a reaction against Marxian political economy as it argued that markets create harmony, not conflict. Human beings were assumed to be rational and selfish, as their decisions are solely motivated by expected utility maximisation based on their given and stable preferences. Mathematically deduced from these assumptions about individuals, an analysis of market equilibria arises. These markets work mainly through price mechanisms; their efficiency as well as their potential failures are analysed.

Neoclassical economics quickly became an important school of thought after its birth in the late 19th century, and after the Second World War it became the dominant theoretical approach in most countries. The increase in its practitioners gave rise to many different sub-branches of neoclassical economics, such as general equilibrium theory and neoclassical growth theory. Sometimes neoclassical economics is mistakenly equated to neoliberalism. While there is overlap between neoliberal thought and neoclassical sub-branches, such as monetarism and new classical macroeconomics, the two are not the same. Many economists, among which neo-Keynesians, for example, use and build on neoclassical (microeconomic) models to oppose neoliberal ideas.

To this day, neoclassical economics remains a highly influential approach, in research, policy making and especially education. At the same time many have been arguing for, or predicting, its demise for a couple of decades already (Colander, 2000). New approaches, such as behavioural, evolutionary and complexity economics, are often thought to replace neoclassical economics as core of the mainstream discipline. Whether this will indeed be the future remains to be seen.

Post-Keynesian Economics

Key assumptions and aspects:

- Main concern: Full employment

- Economies are made up of: Individuals and classes

- Human beings are: Following rules of thumb and habits because of fundamental uncertainty

- Economies change through: Animal spirits and government intervention

- Favoured methods: Stock-flow consistent models and econometrics

- Typical policy recommendations: Stabilisation of effective demand through active fiscal policy

Building on older underconsumption theories, Keynesian economics arose during the 1930s in order to explain and develop ideas to solve the economic depression. In doing so, it considerably overlaps with the Stockholm school. Keynesian economics argues that people compare themselves to others and build their decisions partly on rules of thumb and habits, because of psychological reasons and fundamental uncertainty. Effective demand, consumption and investment, therefore, depends to a large extent on animal spirits and herd behaviour. In the post-war period until the stagflation of the 1970s, it was highly influential. This was especially the case for its neo-Keynesian branch, sometimes also called old Keynesian, which synthesised Keynes’s ideas with neoclassical microeconomics and this neoclassical synthesis forms the core of introductory (macro)economics education to this day.

After the 1970s, post-Keynesians (sometimes also called Cambridge Keynesians), who radically broke with neoclassical economics as they constructed a fundamentally new approach to economics with Keynes as main inspiration, became formally organised as a distinctive heterodox approach. At the same time, new Keynesians introduced imperfections in then influential neoclassical (DSGE) models of new classical macroeconomics, and in doing so came to Keynesian (pro-government intervention) rather than new classical (free-market) conclusions. Theoretically, however, they are furthest removed from Keynes’ own work and thinking.

2. Interdisciplinary Economics

The economy is not only studied by economists; other disciplines also have much to contribute. While this may seem strange at first, it is good to realise that academic disciplines have historically been the field of power struggles between different groups of scientists. Often, the ones who were forced out of the discipline, often for personal, practical or worldly reasons, have found a home elsewhere. For instance, some economic perspectives mentioned above, such as social network analysis and field theory, were developed by economic sociologists rather than economists and are currently also mainly practised by these academics.

In the online resource Interdisciplinary Economics, we provide an overview of the most relevant economic approaches found in other disciplines. We briefly discuss the histories of and different approaches practised in the following economic subdisciplines:

- Economic Sociology

- Economic Anthropology

- Economic Geography

- Political Economy

- Economic History

Teaching students the basics of these economic subdisciplines and their approaches has two advantages. First, students gain valuable intellectual tools. Second, these approaches often form a natural bridge between

the disciplines, helping students to communicate and collaborate more easily with other social scientists. Due to space restrictions we are only able to provide one example here: economic sociology. On our website, we offer the other four: economic geography, economic history, economic anthropology and political economy. We also provide more suggestions on interdisciplinary teaching, using the subdisciplines of neighbouring fields.

Economic Sociology

Economic sociology has been an important part of sociology since its origins. Many of its founders, such as Auguste Comte, Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, Georg Simmel and Vilfredo Pareto, wrote extensively on the economy. In fact, most of them can be regarded as both a sociologist and economist (and often philosopher, historian and political scientist as well). After the formation of the discipline of sociology, most sociologists, however, ceased studying the economy, causing the subdiscipline of economic sociology to move to the background.

This rigid division between the two fields came about as a sort of truce, where both economists and sociologists agreed not to study each other’s fields. The origins of this truce are associated with Talcott Parsons and Lionel Robbins in the 1930s (Velthuis, 1999). Economists would solely focus on the means to achieve given ends, while sociologists studied those ends and the values people have. According to this logic, institutional economics was no longer considered to be proper economics, and economic topics should no longer be studied by sociologists. However, with the partial disappearance of institutional economics and economic sociology, large parts of the economy fell outside the scope of any field of study.

This changed again in the 1980s (Granovetter, 1985; Smelser & Swedberg, 2010). The truce to not study each other’s fields was broken because of a revival of economic sociology and the rise of the imperialism of neoclassical economics. Since then, economic sociology has emerged as one of the main fields within sociology and as such it has produced multiple new approaches and insights. The main approaches stemming from economic sociology are social network analysis, the neo-institutional approach, field theory, cultural approaches, and performativity theory. These different approaches have in common that they all analyse how markets are socially constructed with the help of state structures, social relations and cultural norms. In other words: how they are embedded in society. There is, for example, a strand of research that investigates how the lifestyles and morals of people shape what they do, and do not, buy (see online).

3. Pragmatic Pluralism

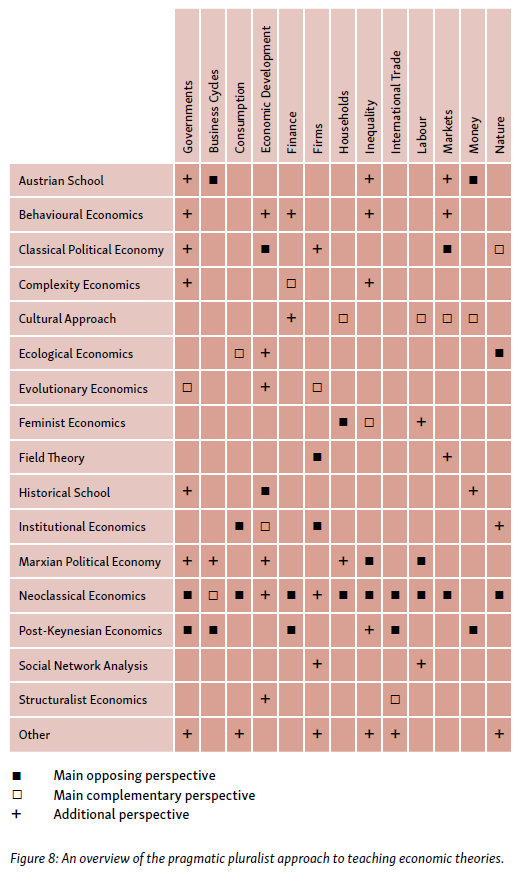

This building block is coupled with Tool 1: Pragmatic Pluralism, which further fleshes out the approach by suggesting which ideas and insights seem to us most relevant to teach in specific courses, such as Labour or Financial Economics. The core of that resources chapter is a table connecting theoretical approaches to thematic areas, followed by a few pages describing the various ideas and insights by the most relevant perspectives for every topic.

Overview

As noted in the introduction to this building block, ‘indiscriminate’ pluralism, teaching every perspective on every topic, is neither feasible nor desirable. Fortunately, different theoretical perspectives have different focal areas. Some have crucial ideas about consumption, others focus on the state, yet others concentrate their explanatory power on finance and business cycles, and so on. These differences form the foundation of our approach. Figure 8 shows an overview of these thematic focal areas of the major theoretical perspectives in economics.

To construct such an overview requires three levels of selection: thematic areas, theoretical perspectives and the most fruitful combinations of these. We will discuss each of these in turn.

First, what are the main thematic areas in economics? Here we stay close to the existing categories in economics education, academic fields and policy areas to create an overview of the core fields of study in the wider economic system. This results in a list of thirteen thematic areas, ranging from markets to development, households and nature, which are shown on the x-axis of the table above.

Second, which theoretical perspectives to include? We decided to include only theoretical perspectives which had a relatively established body of research and ideas and have made crucial contributions to at least two of the thematic areas. Since we see economics as centred on an object of study, the economy, rather than something defined by its current mainstream, we included some approaches which are practised more widely outside economic faculties than inside them. The vast majority, however, falls within the economic discipline. This resulted in a list of sixteen theoretical perspectives, which are shown on the y-axis of the table.

In theory, this could result in an overview of 13×16 topic-approach combinations. However, as stated above, different approaches focus on different topics. This brings us to the third level of selection: which schools to teach on which topics? Building on a wide-ranging literature review and the advice of many experts, we selected the approaches that had the most original and relevant ideas and insights on each of the thematic areas. The functionality of a theory was central in this choice.

For each topic, this resulted in two main opposing perspectives, one complementary perspective and a short summary of other useful insights and perspectives. In this way, one could start a course by discussing the debate between the two conflicting approaches in the first half of the course. The third quarter of the course could be devoted to the additional complementary perspective. Finally, in the last quarter, other useful perspectives and insights could be discussed.

With this pragmatic pluralist approach to teaching economic theory, no single approach is dominant but there is also not an impractical excess of theories. Here it is important to note that following our suggestions would imply reducing the teaching time devoted to neoclassical theory. Studies indicate that currently roughly 4/5 or more of economic theory courses are devoted to neoclassical economics (Proctor, 2019). With this pragmatic pluralist approach about 1/5 of teaching time would be devoted to neoclassical economics. This means that there will be more need to focus on the most relevant and important insights of neoclassical theory, and to in turn spend less time on the technicalities of its models.

Cautionary notes

The table previewed above has a number of important limitations to keep in mind. This section sets out three cautionary notes. Firstly, our table should be seen as a starting point. It leaves much room for improvement and will change over time. Secondly, we have presented a limited overview, but it could easily be expanded by adding additional topics and theoretical approaches. Thirdly, the boundaries between various topics and various approaches are heuristics only: the field is interconnected in many ways.

On our first point, as far as we know, this is the first attempt at trying to systematically identify the most relevant ideas and insights on the different economic thematic areas (with a pluralist approach). Combined with our limited knowledge of the various topics and approaches, it is likely to be rough and imperfect. It should not be seen as a complete overview, but rather as a starting point and an illustration of how such a pragmatic pluralist approach might look in practice. Suggestions for improvement are most welcome. Furthermore, such an overview should never be set in stone as the discipline itself is always subject to change. When new important insights are gained, they should be integrated in education as well. Twenty years from now, the table should look different from how it looks now.

It should also be noted that some topics and theories have more ideas and insights listed than others. Some thematic areas have traditionally received much attention, such as economic development. This results in a larger amount of insights than on less studied areas, such as households, but it is not a judgement on the importance of the topic itself. Equally, some approaches have historically had the benefit of a large research community, such as neoclassical economics, Marxian political economy and the cultural approach. These have thus been further developed and are better represented in the table. Again, this is not to be taken as an endorsement of those schools in general and it could also very well change over the coming decades, as some approaches will be further developed while others will be done less so.

Following on our second point, the table could be expanded to allow for more nuance and detail, and cover more ground. A table of 13×16 is admittedly already quite large, but for trying to compress the entirety of economic thinking into it, it is bound to be too small. Expansion could come from adding topics and approaches as well as from combining the current ones and differentiating within them.

On the x-axis, many other topics could be added, such as health economics, the economics of education and transport economics. Topics like finance and nature could be combined to create new topics like green finance. Within topics like public economics, differentiation could be made between the economics of taxation and the economics of government spending.

The same applies to the y-axis, which lists theoretical perspectives. The regulation school and neo-Ricardian or Sraffian economics could, for example, be added. Combinations between neoclassical and Keynesian approaches could, for example, be made to identify neo- and new Keynesian economics. And further distinctions between original and new institutional economics as well as original and new behavioural economics could be made.

Furthermore, the table could cover more ground by simply adding more insights into the empty spaces in the current 13×16 structure. As said, we intentionally tried to keep it as empty as possible, while capturing the most relevant insights. Where to precisely draw the line between inclusion and exclusion? This is a difficult matter and to a certain degree will always be arbitrary. One could easily imagine including more ideas and insights in the table than we did, or fewer.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that these categories are only heuristic tools to help our thinking. It would be a misunderstanding to suggest that they exist in isolation. The topics and perspectives are fundamentally linked to each other and sometimes the boundaries between them are unclear. Where does the topic ‘firms’ end and ‘labour’ begin? How exactly should we separate ‘money’ from ‘finance’?

While we suggest focusing on specific topics and approaches in different courses, we think it is also important to pay attention to how they are connected and together make up a larger economic whole. These fields do not exist in isolation of each other, nor do their associated insights. To take an example: the new insights in finance from Hyman Minsky had important consequences for those studying business cycles. His core insight was that financial markets had their own dynamics. Rather than simply following developments in the real economy, financial markets could cause huge changes in the real economy. His ideas on the mechanisms surrounding debt accumulation by private sector businesses, financial actors and households proved to be crucial in understanding the financial crisis of 2008 and its causes. In other words, the topic of finance is important to understand for the related field of business cycles.

Just as topics are often connected and difficult to separate, perspectives at times are also strongly linked to each other. Some ideas can even be attributed to multiple perspectives at the same time. So while perspectives sometimes might be in conflict with each other, they also often agree with each other. For brevity and clarity, we included every idea only once in the table. However, in the explanations below the table we discuss when an idea is shared by multiple perspectives.

An example: Finance

To show how this table works in practice we consider the topic of finance as an example. As shown in the table, the following perspectives seem to have made the most relevant contributions:

Main opposing perspectives:

■ Post-Keynesian economics: Animal spirits shape market movements

■ Neoclassical economics: Banks are rational intermediators

Main complementary perspective:

□ Complexity economics: Systemic risk

Additional perspectives and insights:

+ Behavioural economics: Systematic irrationality

+ Cultural economics: Analytical constructs shape the market

Post-Keynesian and neoclassical economics represent two long-standing perspectives on the role of finance within the economy. The first approach, currently strongly linked to post-Keynesian economics, is more inductive in nature and makes use of accounting, or stock-flow consistent, models, which strive for completeness in capturing all flows (transactions) and stocks (balance sheets). The second approach, associated with neoclassical economics, is more deductive and uses equilibrium models, which only include variables that are theoretically deemed to be important in an economy defined by optimal outcomes (equilibria). The latter approach sees the non-financial economy and rational individual behaviour as key, arguing that money is primarily a unit of account and that finance can be excluded from standard macroeconomic models. The financial sector is a passive rational intermediary between savers and investors that enables efficient capital allocation. The former approach, in contrast, emphasises the importance of monetary flows in modern economies and dynamics at the system, rather than individual, level. It argues finance has an active and innovative role and that financial decisions depend on animal spirits because of fundamental, or Knightian, uncertainty that makes it impossible to calculate probabilities for future events.

In the main complementary perspective, complexity economics, financial booms and busts are understood as self-reinforcing asset-price changes, which are prevalent but unpredictable as the decisions and forecasts of many individual agents in complex networks go through phases because of their interactions and feedback effects. An important topic is therefore systemic risk, which is the risk associated with the financial system as a whole, as opposed to individual banks, companies or firms, and thus is concerned with interlinkages and interdependencies. Countering earlier popular ideas that diversification and deregulation are generally desirable, this line of research focuses on the risks associated with interconnectedness and ever more sophisticated financial instruments.

Finally, behavioural and cultural economics provide additional insights into how finance works by focusing on psychological, cognitive and social processes. Behavioural economics, or rather behavioural finance, focuses on how people systematically make errors because of their limited cognitive capabilities and how this influences financial markets. The cultural approach, as practiced by various economic sociologists and anthropologists, focuses on how economic ideas can be performative in the sense that they can shape the phenomena they describe and thereby bring reality closer to their theory. One example of this, is how the neoclassical Black-Scholes-Merton model of option pricing initially poorly described pricing patterns, but later on became empirically successful as market participants began to use the model to trade (MacKenzie, 2008).

4. Practical Suggestions

How can this pragmatic pluralist approach be implemented in practice? In this section we discuss the choice between organising courses around topics or around perspectives.

Courses on topics or perspectives

Within the pragmatic pluralist approach, there are the two options: to organise the key insights by topic or by perspective. ‘By topic’ means that a programme might have separate courses on labour economics, financial economics, public economics, and so on. ‘By perspective’ implies a programme built out of courses on institutional economics, neoclassical economics, Keynesian economics, and so on. In theory, both of these programmes could cover exactly the same ideas and material. Still, there are some important differences between the two options.

Firstly, the two options have different consequences to students’ learning trajectories and their subsequent ability to see the connections between approaches and topics. Placing perspectives at the centre of courses emphasises the theory, while organising courses around topics focuses on the real-world topic as daily life is organised around topics. When a full course is devoted to a perspective, it is likely that this way of thinking will stick with students. If a course is organised around a topic, on the other hand, it is more likely that specific knowledge concerning that topic will be remembered. Focusing on topics also allows us to more easily incorporate real-world knowledge. As such, the choice seems between placing emphasis on understanding a way of looking at the economy or understanding a part of the economy.

There is, however, also another dimension to this choice. When courses are organised around theoretical frameworks, the links between topics are clearer. If topics are put at the centre of courses, it becomes clearer how perspectives complement and contradict each other. The choice is thus between putting emphasis on understanding the topics and seeing links between perspectives or focusing on perspectives and seeing connections between topics.

Secondly, there are practical choices to make. There is a functional advantage to organising courses around topics: it requires less change in existing course structures. Current programmes generally do provide education on a broad range of topics, but focus almost exclusively on the neoclassical perspective. As such, courses are generally already organised around topics. To implement a pragmatic pluralist approach would thus entail pluralising existing courses. If, on the other hand, one chooses to organise courses around perspectives, current courses would have to be replaced by new courses each focused on a different approach.

However, there is also a practical advantage for organising courses around perspectives. Often, it is easier to find academic staff who are knowledgeable in one perspective, who can then apply their perspective to different topics. It can be harder to find teachers who have broad knowledge of a topic and the different perspectives on them. When this is indeed the case, then teachers specialised in certain approaches could be hired to teach courses on them. The reverse, pluralising existing courses organised around topics, would require current teachers to become knowledgeable of the different approaches to topics they teach about. An alternative is to invite academics from other departments or universities to teach a few guest lectures on the perspectives in which they have specialised.

Finally, there is also a danger in organising courses around perspectives, especially if this is implemented piecemeal. The impression can arise that all perspectives, except for the currently dominant neoclassical one, are just ‘nice extras’ that can be taught all together in one additional course, possibly as an elective for those who happen to be interested in it. In an extreme case, the programme would thus change from being exclusively neoclassical to one in which everything is still neoclassical except for one course on “alternative” or “heterodox” approaches.

The point is, however, that these other approaches are not some enjoyable, exotic add-ons. They are crucial for students to learn about as they contribute key insights into how economies work. Without them, students lack important knowledge and remain blind to crucial aspects of economies. In sum, having one course on other perspectives, can give the false impression that they are ‘covered’. Much more attention is needed to properly teach the various important insights – just as substantial time is needed to teach the relevant neoclassical insights.

Teaching Materials

Especially since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008, a wide variety of textbooks has been published to facilitate topic-based pluralist economic teaching. Following every topic-summary in the online resources for this book (finance, labour, nature, etc.), we suggest literature for that specific topic. A few of these textbooks deserve specific mention, because they are useful in teaching several of the topics and approaches. We will introduce them in order from introductory to advanced.

- Economics: The User’s Guide by Ha-Joon Chang, from 2014. This book provides a brief and accessible pluralist introduction to a broad range of theoretical insights the discipline has to offer. While theoretical, this book is never dry. It is clearly written and has a very succinct style.

- Rethinking Economics: An Introduction to Pluralist Economics by Liliann Fischer, Joe Hasell, J. Christopher Proctor, David Uwakwe, Zach Ward Perkins, Catriona Watson, from 2017. This collection of essays provides an accessible introduction into post-Keynesian, Marxian, Austrian, institutional, feminist, behavioural, complexity and ecological economics.

- Exploring Economics: www.exploring-economics.org/en/. This website provides sharp and helpful introductions into the different economic perspectives and furthermore gives many useful overviews of related teaching materials, videos and existing (online) courses.

- Principles of Economics in Context by Jonathan Harris, Julie A. Nelson and Neva Goodwin, most recent edition from 2020. A useful textbook that treats much of the traditional content, but also consistently discusses the social and environmental challenges inherent in economic questions.

- Economics After The Crisis by Irene van Staveren, from 2015. This well-written textbook describes twelve central topics in economics at an introductory level, each from four different perspectives: the neoclassical, institutional, social and post-Keynesian perspectives.

- The Economy by the CORE Team, from 2017. This highly successful textbook, freely available online with additional resources, provides a treasure trove of empirical data, context and recent research.

- Introducing a New Economics by Jack Reardon, Maria A. Madi, and Molly S. Cato, from 2017. This ground-breaking textbook introduces many of the core issues in economics today and weaves together pluralist theory and real-world knowledge in an eminently readable way.

- Economic Principles and Problems: A Pluralist Introduction by Geoffrey Schneider, from 2021. A lively entree into the world of economic ideas, capitalism, markets and government policy.

- Political Economy: The Contest of Economic Ideas by Frank Stilwell, most recent edition from 2011. This well-written textbook provides a good introduction to economic ideas from multiple perspectives, with particular attention to classical, Marxist, neoclassical, institutional, Keynesian and more recent insights related to capitalism.

- Foundations of Real-World Economics by John Komlos, from 2019. This textbook is perhaps the most critical of this list, providing a sharp criticism of the neoclassical school as well as providing a wealth of empirical data and findings.

- Capitalism: Competition, Conflict, Crises by Anwar Shaikh, from 2016. This impressive and extensive book covers many traditional economic topics and compares multiple perspectives on each including classical, Marxian, neoclassical, Austrian, Keynesian, complexity and several others, as well as testing them against empirical data. Not light reading, but very much worth it.

- The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics: Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism by Tae-Hee Jo, Lynne Chester, and Carlo D’Ippoliti, from 2017. This collection of essays discusses a great variety of economic topics and theories, from theories of production, value and prices, to theories of finance, the environment, and the state.

- The Microeconomics of Complex Economies: Evolutionary, Institutional, Neoclassical and Complexity Perspectives by Wolfram Elsner, Torsten Heinrich, and Henning Schwardt, from 2014. This innovative textbook makes readers familiar with new insights coming from frontier mainstream economic research, with particular attention to game theory, agent-based modelling, system dynamics, and empirical realities.

- Macroeconomics by William Mitchell, L. Randall Wray & Martin Watts, from 2019. This ground-breaking and much-discussed textbook written by three leaders of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), describes in detail the history of economic thinking about the state and macroeconomy as well as recent theoretical and policy debates.

- Handbook of Alternative Theories of Political Economy by Frank Stillwell, David Primrose & Tim Thornton, from 2022. A wide-ranging cutting-edge collection of essays on the different ways of understanding the economy, introducing readers to various theoretical approaches such as institutional, ecological, cultural, postcolonial, and neuroeconomics.