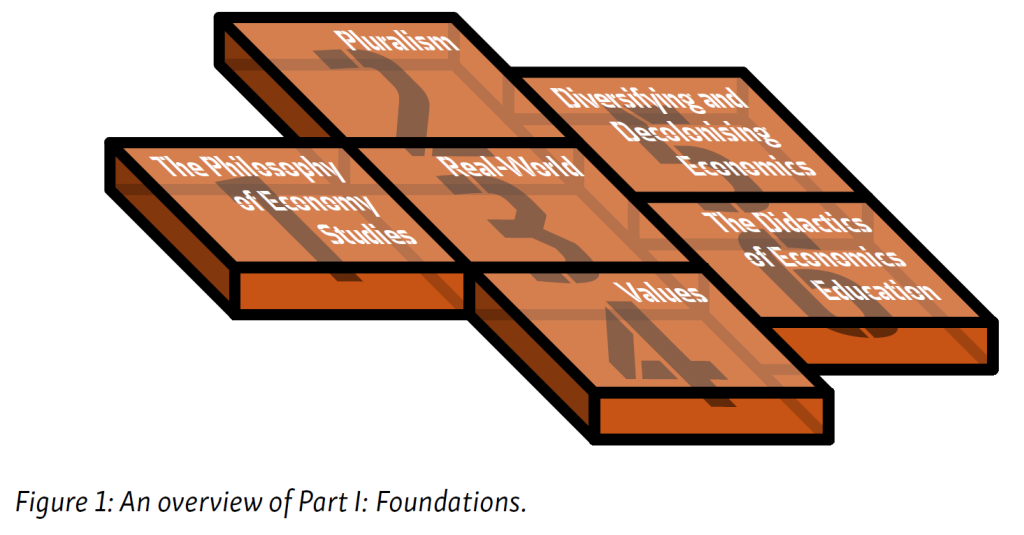

The Foundations:

This part lays the groundwork for the rest of the book. It starts with the central philosophy of the book, explaining the title ‘Economy Studies’. From there, we set out three principles that provide a backing structure for the ten building blocks, which form the next part of the book. The next chapter discusses the need to diversify and decolonize our discipline. We end this part with a brief chapter on didactics, suggesting three points of attention regarding the practice of economics teaching.

The Philosophy of Economy Studies

When designing courses in economics, or even an entire programme, there are endless choices to be made: central subject matter, theoretical focus, style of teaching, what materials to use, how to sequence courses and what to test students on. In the chapter Philosophy, we start with the question that lies at the foundation of all these choices: what should economics education focus on? We broadly identify two answers to that question. Answer A: organise education around a specific method of analysis or way of thinking. Answer B: organise it around a subject matter.

Answer A implies separate programmes for the neoclassical approach to human life and society, programmes for the institutional approach, others for the Marxian approach, etc. We explain why in this book we instead choose answer B: a programme centred on a specific subject matter. Political science focuses on politics. Biology studies living organisms. Economics, then, focuses on the economy. Subsequently, we define what we mean by ‘the economy’, discuss where its boundaries lie and how we might deal with its interfaces to other aspects of the world, such as the political, the social and the ecological.

Principles

In the following three chapters of part I, we set out the three main principles of our framework: Pluralism, Real-World and Values respectively.

The first principle, Pluralism, focuses on the current dominance of a single approach in mainstream economics education, and our contrasting argument for theoretical and methodological pluralism. Learning to use analytical tools such as theories and research methods is the primary purpose of an academic education. We argue that a truly academic education requires a foundation of pluralism: the side-by-side use of fundamentally different, incommensurate approaches to studying the economy. We set out two basic reasons to support such pluralism: it helps students to gain a richer diversity of insights, and it gives them a clearer perspective on the limitations of any single approach, thus facilitating critical thinking.

The second principle, Real-World, concerns the current focus on mathematical abstraction and methodological techniques. We suggest focusing more attention on the real-world economy instead. ‘Real-world economics’ has long been a core demand of the Rethinking Economics movement. It is an ideal that seems self-evident; who would actively reject the real world in their teaching? Still, it is not easy to put into practice. We set out several forms of concrete knowledge about the real world which we believe to be crucial, and provide suggestions on how to implement this in teaching.

The third principle, Values, discusses the notion of value-free science. There is a tendency to try to banish normative issues entirely or contain them in an isolated course on ethics. This leaves students blind to the normative aspects of economic topics and unable to articulate moral dilemmas clearly and critically reflect upon them. Values, our moral principles and beliefs, are an integral aspect of economic dynamics, and deserve a central place in economics programmes. In fact, besides sheer curiosity, they are the entire reason we study economics, and the reason that it is the most prominent social science today: economic dynamics matter for almost everything we care about. This principle is about helping students to become aware of the value aspects of economic questions and to be comfortable with discussing them, in their role as an academically trained thinker and researcher. That does not mean making everything normative. It means learning to identify the normative and positive, seeing underlying values when they are relevant and focusing on the normative aspects of concrete economic issues, rather than only discussing general ethical philosophies.

These three principles overlap with the old idea of a tripartite distinction within economics (Colander, 2001; Keynes, 1891). Real-World is related to the art of economics, also called applied economics, which is about concrete actual cases and how to deal with them as economists. Pluralism is most closely related to the science of economics, sometimes called positive economics, which is concerned with analytical tools for understanding how economies work. Finally, the ideas in the chapter Values build on the ethics of economics, also known as normative economics, which is concerned with judgements of importance and value.

The three do not exist in isolation from each other; they are connected in various ways. For instance, the real world cannot be seen directly but only through lenses that allow focus: analytical tools. Using a diversity of lenses helps to understand it better (pluralism). However, even then, we need to be aware that embedded and sometimes hidden inside these different tools, lie different values. We may try hard to be neutral, but what we observe in practice is coloured by our own personal views.

What should be the balance between these three principles in terms of teaching time? Academic tradition tends to focus nearly all of its attention on teaching analytical tools. While we agree that analytical tools deserve the majority of students’ attention, we feel a more equal balance is necessary. A good economics education includes explicit discussion of the normative aspects of issues, and is built on a base of knowledge of the real world. In fact, even if pure analysis is all you want to teach, your teaching will be improved by including the other two principles. Students will be more motivated and analytically sharpened by the real-world material, and better able to separate judgements from analysis thanks to the clarity about values.

Diversifying and Decolonising Economics

Following the principles, we discuss the problem of diversity in economics. Our discipline has historically been dominated by white upper- and middle-class men from western Europe and the US, and is still so today. This has led to severe biases in our body of theory and in the teaching practices of our field. The ideas of female, global south, ethnic minority and lower-class scholars have frequently been ignored, both in research and in education. The same applies to their economic realities, values, interests and ways of organising economic processes. In addition, the existing culture and structure of the discipline make it hard for women, ethnic minorities and people from a lower socio-economic class to enter.

In this chapter, we provide a brief overview of the problem. We also discuss several potential causes, weighing the evidence on each of them. Finally, we discuss several paths towards diversifying and decolonising economics. This will not only help marginalised groups, important though that is. It will also make economics education itself better for all students, offering them a broader, more realistic and more relevant set of ideas and realities.

The Didactics of Economics Education

We end the Foundations part with a chapter on the didactics of economics education. Improving economics education is not simply a matter of changing what is taught, but also how it is taught. A good course is more than just a good syllabus: it requires effective teaching. The chapter focuses on three didactical issues that are of particular relevance for economics education: communication and collaboration, open and critical discussion, and diversity in teaching techniques.