A tool to scan existing programmes and identify major gaps, using the Economy Studies building blocks.

Since most of us do not have the luxury of designing programmes from scratch, this chapter lays out how existing curricula can be reviewed and improved using the building blocks developed in this book. Such

a curriculum review helps indicate what is missing in the current programme and what might be ways to improve it.

Using the resulting overview, staff and students can make personal and collective judgments as to which things they find most important to improve and where to focus their activities on. This can help both students and faculty to work with the existing curricula and improve them.

This chapter sets out the steps of the curriculum review tool, and applies them to the Harvard undergraduate program in economics as a demonstration of the method. The first step is a rough overview: scan per building block whether any courses cover parts of it. The second step is more detailed, and looks within the building blocks, to see which of their various sections have been covered. The third and final step sets out how to go from this curriculum overview to more concrete recommendations for improving the programme.

The methodology for analysing curricula described in this chapter differs markedly from existing methodologies (Proctor, 2019), mainly in that this methodology is less time-consuming. Rather than reviewing what is included, it focuses on what is absent in existing programmes.

The steps outlined below provide a simple guide to reviewing existing curricula, using the Harvard undergraduate economics programme of 2018-2019 as an example.

Step 1: Overview by Building Block

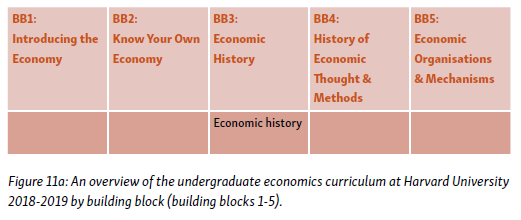

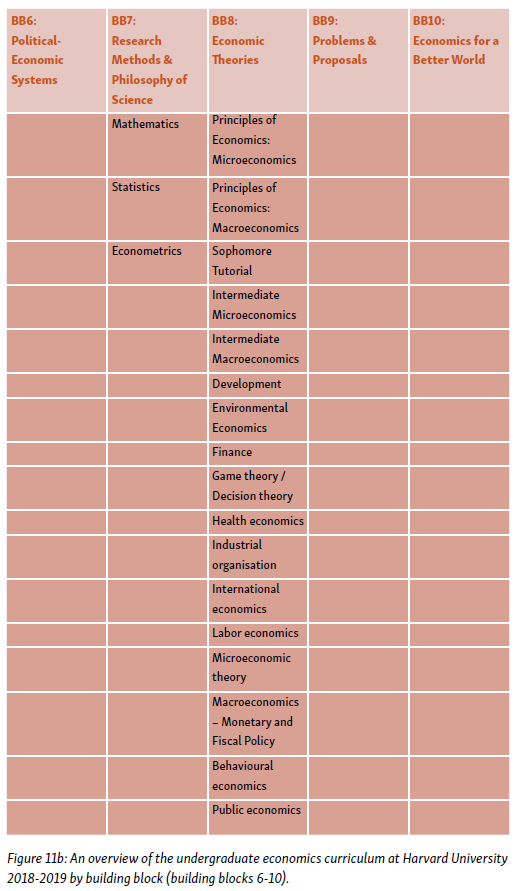

The first step is to make a column for every one of the 10 building blocks. Assign every course of the programme in question to one or several of the columns. This step gives an overview of what types of skills and knowledge the current programme emphasises, and which building blocks are not covered in the programme. It thus allows you to see where most headway could be made.

As the above overview shows, the undergraduate economics curriculum at Harvard University 2018-2019 has a strong focus on Building Block 8: Economic Theories. Building Block 7: Research Methods & Philosophy of Science also gets serious attention with three mandatory courses. And besides these analytical tools, there is one elective course on Building Block 3: Economic History.

The overview also makes clear that various building blocks are still missing, which serves to identify low-hanging fruit for improvement of the programme. Building blocks 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 10 are currently not covered. In order to improve the curriculum, one or more of these building blocks could be incorporated. For instance, to provide students with a more solid grounding in the normative aspects of economic questions, one could advocate for including a course on Building Block 10: Economics for a Better World.

Whilst Harvard University has been chosen here as an example, its curriculum and the elements missing are hardly unique. Therefore, the overview here should not be seen as a critique of Harvard University, but rather as an analysis of what most economics programmes currently and often leave out. Colander and McGoldrick (2010, pp. 29-30) summarise the currently most prevalent curriculum structure:

“At most schools, the undergraduate economics major almost always includes one or two introductory courses (usually called principles of microeconomics and macroeconomics), intermediate theory courses in both microeconomics and macroeconomics, one or two quantitative methods courses covering basic statistics, regression models and estimation techniques, a few elective upper-level “field” courses and ideally a senior seminar or capstone course that includes an extensive research and writing component. Often, there is a calculus requirement, but that requirement is often designed more as an analytic filter for who can major in economics than as an actual needed requirement. The introductory and intermediate microeconomics courses concentrate on presenting a constrained optimization model in either a geometric or calculus format. The introductory and intermediate macroeconomics courses concentrate on presenting geometric AD/AS and IS/LM models.”

Step 2: Overview Within Building Blocks

The rough overview described above is useful for identifying the main elements which are currently missing in a curriculum. However, a more detailed overview might be necessary, which delves into the building blocks, asking which of their core features are included and which parts have been left out. This fine-grained analysis helps students and faculty to see the focal points or strengths of the programme and its individual courses more clearly, as well as pinpointing where there is room for improvement.

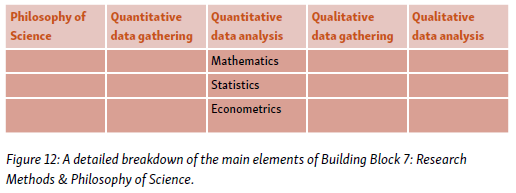

To create a more detailed overview, compare the courses in every building block column (from step 1) with the main elements of that building block, as shown on the first page of that building block’s chapter in this book. For instance, for the building block column Research Methods & Philosophy of Science, analyse whether the following elements are included: (a) Quantitative data gathering (b) Quantitative data analysis (c) Qualitative data gathering (d) Qualitative data analysis (e) Philosophy of Science.

As step 1 of this analysis showed, the Harvard programme does teach material from Building Block 7: Research Methods & Philosophy of Science. However, the more detailed breakdown, allows us to see more precisely which elements of this field are taught. Table 2, above, shows that all emphasis is on quantitative data analysis. The other main elements of Research Methods and Philosophy of Science, quantitative data gathering, qualitative data gathering, qualitative data analysis, and philosophy of science, are not included in the programme.

Based on these findings, one could argue for the creation of a course in qualitative research, philosophy of science or in quantitative data gathering. Alternatively, if there were no room for an entire new course, such elements could be incorporated into existing courses. The existing Methods courses at Harvard could, for example, incorporate discussions about philosophy of science and/or quantitative data collection.

Thus, the detailed overview (step 2) helps to identify gaps within the building blocks which do not become visible through the rough overview (step 1). One could also go into more detail than given here by, for example, looking at what specific quantitative data analysis methods are included in the programme and what methods are left out. Such analysis might show that descriptive statistics and regression analysis are included, while network analysis is not. Students and staff can then determine for themselves which level of detail is useful for them to pursue when reviewing a curriculum.

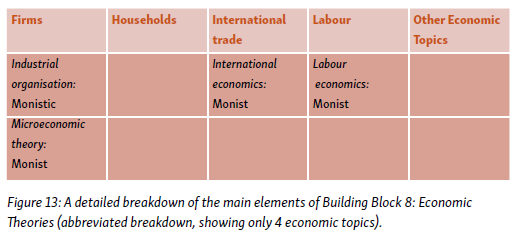

A particular note on Building Block 8: Economic Theories is necessary, as this building block is substantially larger than the others, as well as being the building block where most currently taught courses fit in. In essence this building block consists of two elements: (a) the topics, and (b) the theoretical perspectives. First, one checks which topics are taught and which are not. This gives an idea about which economic topics that are not covered in the programme. Then, for the topics that are taught, one can analyse whether this is done in a pluralist or monist way. Or in other words, whether it does include multiple perspectives or not.

With the help of the table provided in Tool 1: Pragmatic Pluralism, one can transform courses to be taught in a more pluralist fashion. Again, a more detailed analysis is also possible. Instead of simply looking at whether the teaching is done in a pluralist way, one could analyse which specific perspectives are included and excluded. Such an analysis gives deeper insight into the specific ideas that are taught, and which are missing.

As can be seen in table 3, the Harvard programme does include courses on firms, international trade, and labour. However, it does not teach students about households. Furthermore, whilst it teaches students about firms, international trade, and labour, it does so in a monistic way, meaning it only includes one perspective. Other faculties or programmes will often have at least one or more courses which are pluralist in their treatment of economic theories.

Step 3: Formulating Recommendations

By using the quick scan methodology described in this chapter, it is possible to identify areas of serious improvement to an existing programme with only a few hours of work. For the Harvard programme, our recommendations would include the following:

- Incorporate new material on building blocks 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10. In particular, discuss values and aspects of the real world, rather than limiting the programme to theories and methods only.

- Incorporate additional theoretical approaches in the theory courses (see Tool 1: Pragmatic Pluralism).

- Incorporate additional work on research methods, including qualitative research methods, quantitative data gathering and philosophy of science.