1. Rethinking Economics Education

Humanity is wealthier, more connected and more technologically advanced than ever. Access to healthcare is rapidly expanding and poverty levels keep dropping in most parts of the world. At the same time, societies around the globe are facing a multitude of challenges. To name a few: climate change, biodiversity loss and resource depletion, growing inequalities and power concentrations, economic instability and soaring levels of private and public debt, ageing and migration, social polarisation and rising authoritarian nationalist populism. And, back on the table since 2020: pandemics.

Tackling such challenges requires a deep comprehension of the economy, which the current system of economics education does not sufficiently provide. Economists need a real-world understanding of how various industries work, how they are intertwined with each other, how economic power works, what roles states play and how these are embedded in our society at large. It also requires open minds which can look at issues from a variety of perspectives. A single theoretical framework cannot provide the answers to every question. A range of approaches which prioritise different methodologies, assumptions, units of analysis and outcomes, is necessary for gaining a good understanding of the economy and its issues. Economists need to be able to think critically, select the tools which are most relevant for the context and problem at hand, and understand the limitations and uncertainties of the conclusions that they draw from them. Finally, it requires an awareness and an explicit discussion of the moral dilemmas and normative trade-offs involved in economic decisions. In short, economists have a lot on their plate.

Economists also have a lot of influence, for good and for bad. Firstly, as key policy experts and advisors, economists largely run many of the most powerful public-sector organisations in the world: central banks, ministries of finance, social and economic affairs, the IMF and the World Bank. In the private sector, economists co-direct the behaviour of banks and other large companies. Secondly, the economic ideas that float around most prominently in our society exert an influence far beyond the formal advisory reports of professional economists, guiding decision-making of citizens everywhere. Economic thinking influences even those who do not become economists, as economists have a central role in the public debate and many citizens are taught basic economics in secondary or tertiary education.

The growing societal importance of economists and economic ideas has sparked a lively debate around the content and structure of economics education. A worldwide movement of students and academics calls for more pluralist, real-world focused and socially relevant programmes that would enable economics graduates to better understand and tackle the economic issues that the world faces today. This movement has accelerated over the last decade, spurred on by the global financial crisis of 2008, the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under names such as Rethinking Economics, Netzwerk für Plurale Ökonomik, Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), International Student Initiative for Pluralist Economics (ISIPE), International Confederation of Associations for Pluralism in Economics (ICAPE), Diversifying and Decolonising Economics, Economists for Future, Reteaching Economics, and Oikos International, these groups come together for dissent, discussion, self-education, action, campaigning, disseminating ideas and engaging with wider audiences.

Research by these groups indicates that many current programmes are not sufficient to prepare students for their future roles in society. They are often organised around the notion of ‘thinking like an economist’: training students to think exclusively from the neoclassical perspective and having skills in econometrics, while neglecting other valuable theoretical approaches and research methods. Furthermore, these analytical tools are taught in an overly abstract way and are presented as being value-free.

These groups and others have also produced a growing amount of innovative teaching material, beyond how economics programmes are traditionally structured. From online educational resources such as the open access CORE project and the bottom-up e-learning platform Exploring Economics, to multiple new pluralist and real-world focused textbooks. Many departments have introduced a wealth of new courses, or even started entirely new programmes.

2. This Book: Purpose and Overview

What has been missing so far in this field is an integral approach for constructing economics curricula and courses. This book aims to fill that gap. We bundle the ideas and materials of renewal and reform into a coherent multi-level vision for economics education: its overarching structure, its goals and its principles. We also provide the concrete building blocks for this in terms of academic content, including detailed overviews of teaching materials and practical suggestions. Finally, we translate these to the level of actual programmes and courses, providing a wide range of practical tools for implementation.

This entire book carries a CC-BY Creative Commons licence, which means that any part of the book may be freely copied, redistributed, remixed, transformed or built upon, without restrictions. As such, our proposal

for a new integral approach to economics education can also be adopted and used partially, rather than being accepted as a whole. Each idea and suggestion can be judged and incorporated independently. You can totally disagree with principle 1 yet support principle 3. Or you might find little value in building block 5 and yet fall in love with building block 9. That’s the idea: it’s modular. Thus, the book as a whole can be used as a source of inspiration and overview of options for improving and renewing economics education.

The first part of the book, Foundations, sets out our philosophy and the three guiding principles that should underpin any economist’s education. In contrast to the currently common approach of teaching students to ‘think like an economist’, the Economy Studies approach is this: We envision an education where economics is not centred on a specific method of analysis or thought, but rather centred on a study matter, the economy. Economies can broadly be described as open systems of resource extraction, production, distribution, consumption and waste disposal through which societies provision themselves to sustain life and enhance its quality.

Based on this philosophy, we formulate three principles: Pluralism, Real-World and Values.

First, a discipline centred around a single subject matter requires a plurality of theoretical frameworks: one single set of basic assumptions is not enough to understand such a multifaceted subject matter. Here it is important that students learn which ideas are compatible with each other and which are in conflict with each other. Some of these theories fall within the current economic mainstream, others exist on its fringes, and yet others are currently at home in other disciplines. It also implies a plurality of research methods, from basic statistics and regression analysis to interviews, network analysis and survey analysis. Such pluralism means that there is no single dominant framework, which might be more difficult for those receiving economic advice, but is ultimately beneficial for the quality of analysis and the resulting decisions.

Second, the notion of a programme centred on the subject matter of the economy implies a continuous and conscious orientation towards the economy as it exists in the real world. Students benefit from studying practical questions and gaining concrete knowledge, not just abstract analytical tools. For instance: How is the German car industry structured? What hurdles does the global energy transition face? What happens at a central bank? The Real-World principle ranges from studies of economic sectors and key institutions in the local or (inter-)national economy, to the histories of economies and case studies of specific economic challenges.

Third, we draw attention to the wide variety of normative principles and visions that can guide economic decisions and action, and which are often subtly embedded in economic theories. There is little sense in trying to ‘solve economics problems’ without considering what things exactly are worthwhile or problematic, and what values are at stake. Profits, sustainability, power, equal chances, equal outcomes, job creation, labour conditions, ownership, accountability, GDP growth, wellbeing – what should we focus on?

Economics has historically been, and is still, dominated by upper- and middle-class white men based in the Global North. This has consequences for each of the three principles. In terms of Real-World, it is important to pay attention to the lived economic realities of working-class citizens, women, minorities, and those living in the Global South. For Pluralism, we need to incorporate often ignored but valuable ideas and contributions of lower class, female, and non-western scholars. For Values, it is key to realise that people from different backgrounds have different priorities and values, and work to ensure that these are reflected in the questions we focus on and the theories and methods we use. In sum, we need to diversify and decolonise economics education.

The Foundations part ends with a chapter on didactics. Improving economics education is not simply a matter of changing what is taught, but also how it is taught. Various surveys among employers of economists show that more attention for communication and collaboration skills is needed. There are also worrying indications that economics classes often fail to facilitate open, critical, but also respectful, discussions. Finally, to make economics education more lively, interesting for students and connected to the real world, a greater variety of teaching and examination methods could be used. On all these fronts we provide practical suggestions.

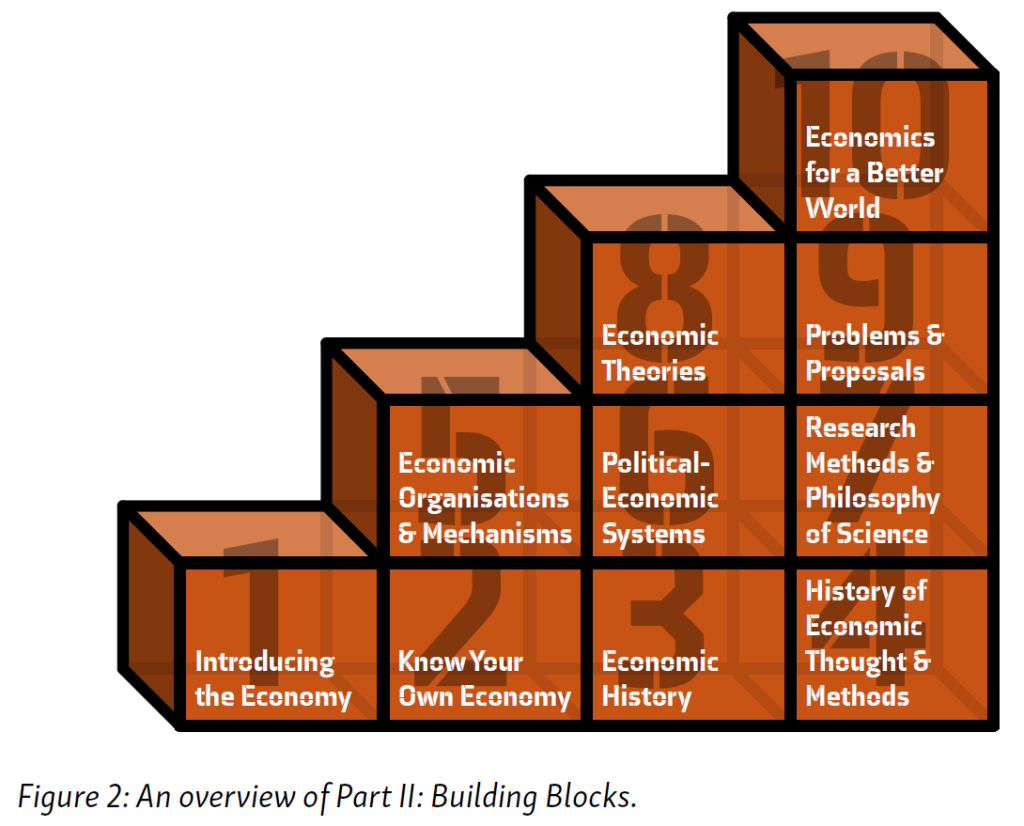

The second part of the book is devoted to the Building Blocks. Where the Foundations part discusses the purpose and principles of economics education in general, the building blocks are more applied: ten thematic areas of knowledge and skills, which form the meat and bones of the Economy Studies course design method. Each of the ten building blocks covers an area of knowledge and set of skills that we see as essential for the education of future economists.

We start out with two building blocks that focus on acquiring basic economic knowledge, one conceptual and one focused on the real world. Introducing the Economy is about getting a feeling for economic matters, discussing what the economy is in the first place, why it is relevant, how it is related to other aspects of the social and natural world, and what societal roles economists have. Know Your Own Economy, on the other hand, has a more concrete focus as it is about knowledge of the actual (national and local) economy and its structures, institutions, and sectors.

The third and fourth building blocks deal with history: History of the Economy and History of Economic Thought & Methods. The fifth and sixth building blocks are more conceptually oriented, dealing with how economies can and have been organised, at micro and meso levels – Economic Organisations & Mechanisms – and at the macro level – Political-Economic Systems.

The seventh and eighth building blocks provide a broad and diverse analytic toolkit: Research Methods & Philosophy of Science and Economic Theories. These two, especially the latter, are relatively large. In most programmes, they will require more space than the other building blocks. Finally, building blocks nine and ten deal with practically contributing as an economist: Problems & Proposals is about analysing concrete economic challenges and formulating or evaluating proposed policies and actions, and Economics for a Better World asks how normative principles and visions can guide action to address the major challenges of our times, and helps students to be reflective of their own role as an economist.

3. Using the Economy Studies Toolkit

These building blocks can be used as templates to create stand-alone courses or modules, or they can be combined in courses. They can be re-ordered, combined or integrated in many ways to suit the specific needs of each programme. For instance, Building Block 3: Economic History could be taught as a stand-alone subject, or integrated with the fourth building block into a course History of Economic Thought and Reality, or integrated as a minor component in an existing Labour Economics course. In our ideal world, these building blocks would be combined to form a wide range

of economics programmes. Different contexts and challenges require differently trained economists.

The third part of the book, titled Tools, provides material that is directly actionable. It starts with Pragmatic Pluralism, a suggested format (including references) for teaching theory in a pluralist manner without drowning students in the enormous diversity of ideas out there. We list thirteen core economic topics and set out for each topic the two main opposing perspectives, a key complementary perspective and additional insights coming from other approaches.

Often there is no space in programmes for completely new courses but there is room for adjustment in some existing courses. In Adapting Existing Courses, we offer ready-to-use sets of suggestions and material to do so, for courses like Micro, Macro, Public Economics and Finance.

The Curriculum Review Tool offers a clear starting point for applying our building blocks to an existing programme. This tool helps identify possible blind spots of a programme and suggests ways to strengthen it. The Example Courses that follow illustrate how the building blocks can be used to create completely new courses. The next chapter maps out several complete Example Curricula, demonstrating how the building blocks might be combined to form a complete bachelor or master programme in Economics.

While this book is primarily oriented towards full economics programmes in academic education, in the chapter Courses for Non-Economists we suggest limited packages of core economic ideas that may be useful for secondary school economics programmes, in an academic minor or for self-study. Finally, Learning Objectives offers tools for designing the learning objectives behind economics courses, starting not from the question ‘what does the teacher know best?’ but from ‘what do the students need to know, to be prepared for their future societal roles?’.

Economy Studies is more than a book. On the website, we offer an extended version of the Pragmatic Pluralism chapter, a broader range of Adapting Existing Courses topics, additional Example Courses, Example Curricula and programmes for non-economists. We also provide background material on each of the Economic Approaches described in this book, as well as neighbouring sub-disciplines such as economic sociology and economic geography. In addition, we provide a more complete overview and discussion of research methods, coordination and allocation mechanisms, and the history of economic thought and methods. Finally, we offer much more extensive lists of teaching materials for each of the building blocks.

Online, we also work together with the INET Education Program, at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. This platform will host free educational resources online, accessible to students, teachers and the general public. This includes video lecture series, syllabi, teaching modules, lecture notes, readings, sample quizzes and exams. The platform will also serve as a center to build up an online community of teachers and learners, working together to improve the way economics is taught and learned. Each of the chapters in this book has a discussion page on that platform.

What kind of graduates would a programme based on these ideas and materials produce? It is important to acknowledge that they would not have all the skills that current-day graduates have. Less mathematical sophistication, less expertise in econometric analysis, less knowledge of neoclassical theory. In exchange for these losses, students gain: a deeper understanding and more concrete knowledge of the economy in which they live and will work. An awareness and understanding of the various ways in which economic processes are organised at the micro, meso and macro levels. Practical skills for investigating and tackling questions of economic policy: understanding the context and choosing the right tools, from a variety of theoretical and methodological approaches. And the ability to argue morally as well as analytically, and to clearly distinguish the two.

With this creative commons work, we hope to inspire economists and all students of the economy to rethink how we learn economics. The economic challenges we face as societies are enormous, so we desperately need well-prepared economic experts and a citizenry able to participate in economic discussions. Economics education has the vital task of preparing these people as best as possible.