Sestriere, August 2021

Dear reader,

This guide was created in 2018 by a superstar group of Rethinking Economics students who had recently published reviews of the economics education for either their university or their country. During the Curriculum Camp 2021 organized by oikos International, we decided to give the guide a new life and also make it applicable to business and management education. So whether you are an economics or business student and you are interested in reviewing your curriculum to push for change, this document can help you do that.

So why change the curriculum in the first place?

Before you get reviewing, here are some reasons to change the curriculum in your university:

- Future-proof your education: take the initiative to get the knowledge, skills, and preparation for jobs that our lecturers don’t even know exist.

- Develop your skills: creating and managing change is a valuable competency, which can empower everyone in your chapter and improve personal satisfaction.

- Create momentum: by driving change, your chapter members, fellow students, and university staff can feel more connected to each other and ready for more challenges.

- Be the change you want to see: New models and perspectives are the basis of the transformation towards sustainability.

- The time is now: Technology is changing so rapidly that traditional classroom instruction is not enough anymore. Students need experiences and holistic education for 21st-century challenges, such as Covid-19 and climate change.

Five easy things you can do now to get started reviewing your curriculum

- Get the word out: Inform, recruit and organize an action group of oikees and friends who are ready to change their education.

- What do you want to change? Think about your courses and set out your vision and goals for change.

- Look into what’s been done before: Get in touch with oikos Barcelona and oikos Copenhagen for insights.

- Speak to your open-minded Professors: Every University has staff you can start a constructive discussion with

- Join the PIR: Contact and get involved with the Positive Impact Rating.

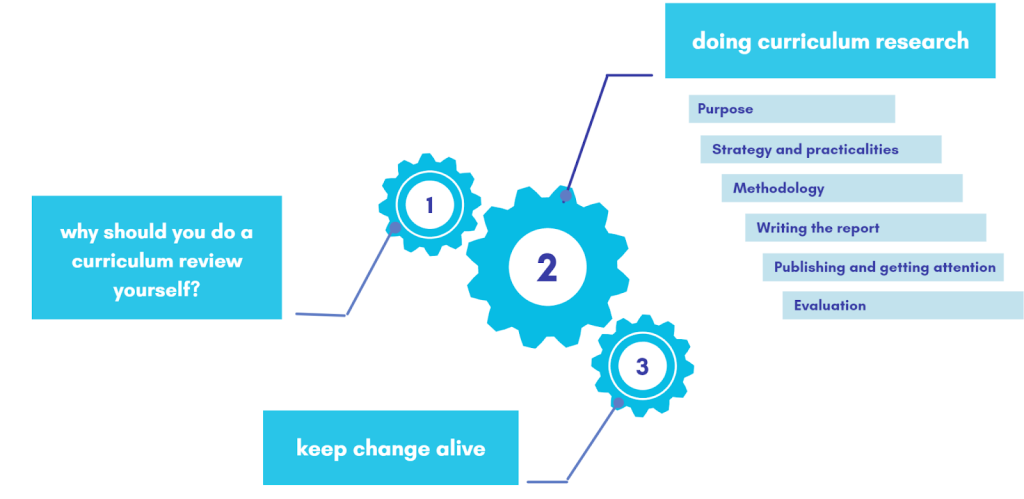

How do you do a curriculum review?

And you already have a community of support! Check out what’s been done before and talk to:

- Check out our Mapping Pluralism report and the other examples of curriculum reviews

- oikos Barcelona are already working on a Curriculum Review Guide – get in touch for ideas and support.

- oikos Copenhagen has successfully made curriculum change happen in Copenhagen Business School.

- The Positive Impact Rating is a student-led survey that provides evidence of the student demands for curriculum change. Contact John and Giuliana for more info.

- Sam de Muijnck and Joris Tieleman have written Economy Studies: A Guide to Rethinking Economics Education which gives you the building blocks for economics education and the Curriculum Review Tool to quickly spot what is missing in an economics programme. Oikos has also developed building blocks for business education.

- Laia from the oikos International team can help point you in the right direction: get in touch with her for ideas, resources and support.

All the best,

Alexandra, John, Laura, Michela, Sam and J.Christopher

Original introduction from 2018:

Recently, the movement for pluralism in economics has published a number of reviews of the curricula used to teach students economics at various institutions. The members of the PEPS-Economie Students’ Association did research into French undergraduate economics curricula by looking at course titles. In 2016 Arthur Jatteau at ISIPE used this framework to do a comparison between countries. Subsequently, German groups have also applied this framework. In Britain the Manchester Post-Crash students have investigated in detail how economics students are tested at 7 universities in the UK and published The Econocracy, a methodology which was later adopted in the Durham University curriculum report Educating Economists?. Finally, Rethinking Economics in the Netherlands published the report Thinking like an economist?, a quantitative analysis which compares the content of the curricula of all nine Dutch bachelor tracks in Economics.

The purpose of the document before you is to set out the lessons learned in these projects. Because if you want to do something similar, it is worthwhile to realize there were many choices, mistakes, discussions and explorations along the way which didn’t make it into the public version – the backstory. This document goes into the process of setting up the research, gathering the data, analysing the results, writing it all out and finally getting the word out! It was written by a small number of people who wrote curriculum reviews, and whilst it partly builds on our own experiences, it is meant to be a general framework for any curriculum review. As the authors of other studies add to this document, it will be further enriched with a variety of angles. In general, there is no ‘optimal way’ to do such research. It depends very much on the situation in your country and university.

This report throws up many, many issues, and asks equally many questions. Please realize that it is absolutely OK if you do not have answers to all of those questions. Do not let that stress you out. All of us who already wrote curriculum reviews also made a fair portion of it up as we went along. As Oliver Burke explained so reassuringly in his Guardian column, most people are totally just winging it, most of the time (google that stuff, it’s inspirational!). The important thing is simply getting to work, and not stopping until you’re satisfied. Good luck!

All the best,

Joris, Sam, Ola, Sally and Eric

P.S. All documents mentioned in this guide can be found in the databank at goo.gl/M6VYJT.

Table of contents

- Purpose

- Strategic decisions and practicalities

- Methodology: doing the review

- Writing the report

- Publishing and getting attention

- Evaluation stage, getting feedback and long-term change

1. Purpose

Before starting off with the actual project, it is important that the organization collectively has a clear idea about why you are writing the curriculum report. Is it to raise awareness about the lack of pluralism, sustainability, diversity, or critical thinking in the curriculum? Is it to promote your organisation or society? Is your report going to be purely descriptive, i.e. no opinion on how the curriculum should be, or should it make a normative statement, suggesting certain principles for the curriculum (see section 3, Choosing review criteria)? Is it to get a better understanding of the current curriculum, its benefits and shortcomings? Is it to make substantial changes to the curriculum in the long or the short term? Do you want to raise a national outcry, or to engender a nuanced local discussion at your university?

The answers to these questions lay the foundation of the project and its direction. For instance, if your primary goal is to create a better understanding of the current situation, then your report should be wide-ranging and incorporate as many sources of information as possible. This was the case in Durham. On the other hand, if you already know what the curriculum is like, but you need proof to publicly get your message out there, then it might be better to have a single source of data, and a very rigorous process producing a few central statistics. The latter was the case in the Netherlands, so that group ended up producing a number of core, easily communicable statistics, but less detailed information and no individual student perspectives.

Having a good idea about why you are writing this report makes it easier to put up clear goals for the project. Usually, it is important to have one main goal, for example to add certain modules to the curriculum, change the exams or the textbooks used. However, there might be possibilities to set up sub goals, e.g. developing the organisation, improve publicity or strengthening the ties to the faculty.

There are important things to consider when figuring out both purpose and goals for the project. Firstly, make sure you are ambitious but still realistic. It takes a lot of time, usually much more than one would think. Many societies have to work on this project whilst studying full time. It is important the what is decided is realistic to achieve when student life hits you. Secondly, it is usually smart to have a good process when deciding goals and the purpose. This might seem obvious. However, often these things are just decided by a handful of people without proper reconciliation and discussion. Having a broad discussion which includes many people in the organisation does not only make more ideas come forward, give a better discussion and better decisions, it will also make sure the purpose and goals are widely understood and properly rooted in the organisation.

2. Strategic decisions and practicalities

Why do you need to explicitly formulate a strategy? To make sure the process of making the report is founded on the purpose and directed towards your goals. There are several aspects that ought to be included in the strategy. Important strategic decisions include the following:

- The process of making this report

- How to approach other actors

- Communication and publicity strategy

We will discuss them in this order.

Process

The strategy should say something about the process of making the report. Who leads the work and what people has the different responsibilities? Who should be included in the process of writing, brainstorm and feedback? What is the timeline and deadlines for the project? If one of the goals is to develop the organisation, it might be smart to recruit new people for the project. If you want to change something in the curriculum, it might be smart to ally with some professors which can give feedback, come with ideas and give advices on how to approach the faculty and other decision makers.

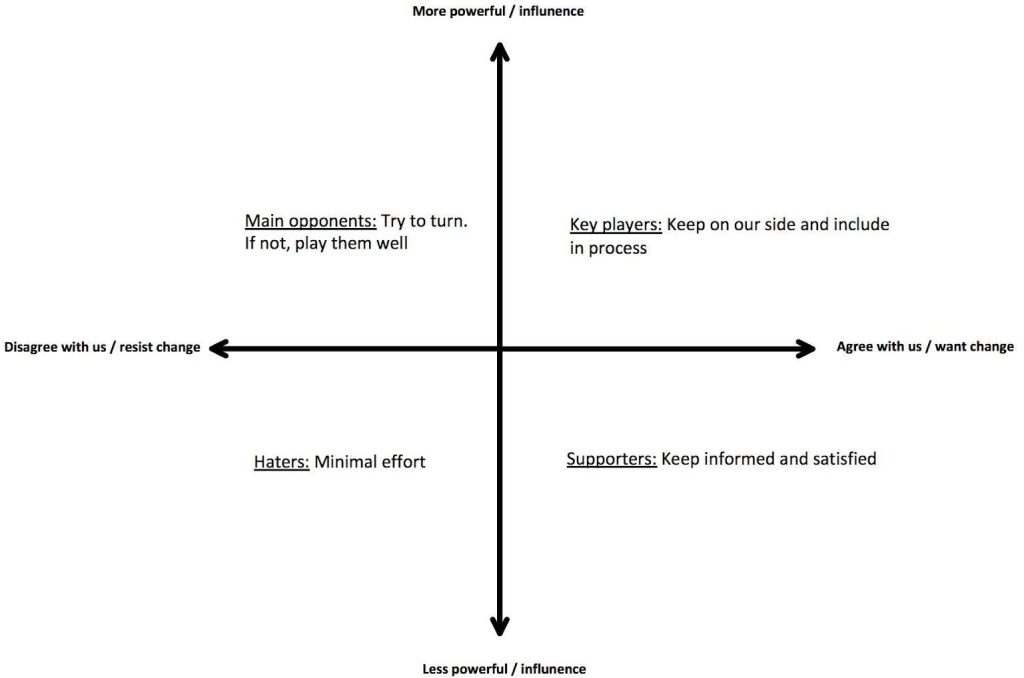

Approach towards other actors

The strategy should also include something on how to approach other actors. This may be the formal program director or their supervisors, the economics or business school faculty, or whoever else has a significant influence on the economics and/or business curriculum. The strategy towards various people or groups should be based on how they view your goals. Do they usually agree with us, or will they give us a lot of resistance when we propose for changes? Who has the power and who means what? It can be useful to use a “power map” to map who has influence, who needs to be influenced and where they stand. Usually, the relationship to actors such as the school faculty will be a long term relationship. Hence, it is important to think about your strategy in a broader context than just this one report. You might write a new report in the future or continue work on your current suggestions.

Communication and publicity

The strategy should also include something on communication and publicity. The work you do, both the process of making the curriculum review and to get the suggestions implemented includes gaining support for your stands. Hence, it is important to communicate in a way influencing them in this direction. What should be your strategy?

A useful metaphor is ‘good cop vs bad cop’. In this context, being a good cop means that you are careful about not upsetting the other actors, but rather approach them politely with indoor voice. Instead of insisting on issues, demand change, putting up sassy slogans and memes, and arranging loud demonstrations, you rather ask for dialogue and offer to help the business school to improve. On the other hand, the bad cop would not ask too many questions, but rather use a loud voice, arrange protest (like happened to Mankiw at his Harvard class when the student walked out of his lecture) or characterize the actor in certain way (such as calling it “autistic”, like students in Paris did).

The most effective strategy will be differ from university to university and from different stages in the process. If you have a faculty that do not want to discuss with you, you might need to raise you voice to get a seat at the table. If you already talk to them quite well, it might push them away if you speak up to loudly. Most helpful, of course, is if you can split these two roles with other organisations. In the Netherlands, for instance, there are some very public figures who were happy to run with our results and do the angry shouting. This allowed the students to be the ‘reasonable’ party, and have constructive talks with faculty.

Independent from your choice of engagement style, it is usually very important to start by creating a narrative where you describe certain premises and concrete issues. This is important firstly to get attention, but mostly to make sure people understand why there is need for change. Why all this demand for change if you don’t experience any problem? To start with, you might say that (putting up premises) when the curriculum is to narrow, with only one dominant school of thought, students will be less reflective and have a weaker understanding of the economy and business. Or you might describe the history and recent development by saying that during the last couple of decades, most economics curricula have become increasingly narrow. On the more concrete side, you might suggest that it is likely that your university is very narrow in terms of theoretical approaches as well, based on the core modules you have undertaken. Or you might point to your latest assessment and point out that they never ask for any reflective or critical thinking. With all these issues, it seems clear – we definitely need a proper review of our curriculum!

During this stage of describing the problem, it might be better to play the bad cop mainly to get more attention and create enthusiasm about your cause. However, you could also see that there is a potential and willingness to change in you faculty, and they just need a bit more convincing. In that case, it might be better to work on the data and facts in a nuanced and thorough way.

In the strategy section, it is important to think about publicity as well – how you’re going to get your message out there. This includes the tone, which platforms to use, posters to hang up on campus, announcements to make in lecture, how to engage people who are not yet involved and so on. This is described further later in the document.

3. Methodology: Doing the review

When you have decided on your purpose for doing the review (section 1 of this document), and what resources you have available (section 2), it is time to decide on a suitable methodology for the review. In this instance it may be very useful to read through the methodologies of previous reports. We will take you through some core decisions to make and ideas to consider.

Quantitative or Qualitative?

An important choice in setting up such research is between qualitative and quantitative research. Most likely you have been speaking out already, on the basis of your own experiences in economics and business education. That would be a crude form of qualitative research. However, student surveys and interviews with professors can be examples of more suitable qualitative research for a curriculum review.

Many of the examples included in this handout are quantitative. Looking at the percentage of exam marks allocated to sustainability, the number of different schools of thought presented in a course, how much of the modules is having a real world approach and the different topics mentioned in a syllabus are all examples of quantitative research. There are many perks of quantitative research: it is more readable and more easily comparable between universities. It also gives your research more credibility, especially considering that a big part of your audience will be economists and/or business scholars, who might regard numbers more as “facts” rather than stories.

However, it is not necessarily easy to create quantitative data. It hurts to squeeze the complex reality of an experience, a course, a theory or an idea into a single figure or statistic, and it always misses more information than it captures. But the purpose of quantitative data is not to fully describe your object of investigation, it is to prove one specific thing about it and contribute something meaningful to the discussion.

In short, to get a truly accurate and detailed picture, the best approach is to combine quantitative and qualitative research, to make sure that you also capture those aspects your quantitative data cannot. However, this is a very high bar to set, and it’s important to make the trade-off between using the limited time you have and producing a great curriculum review. Use your own judgement here.

Data sources

There are many possible data sources for a research project like this. Most of these are available in a google drive here.

- Course descriptions by the professors

- Course titles (ISIPE / Germany / PEPS)

- Course descriptions and handbooks (Netherlands and Durham)

- Course materials

- Lecture slides or handouts for lectures

- Exams (Econocracy and Durham)

- Other summative coursework, such as essay questions (Durham)

- Formative coursework and tutorial/seminar exercises

- Student opinions

- Survey among students (Durham, Cambridge, Italy, Positive Impact Rating)

- Interviews among students

- Personal experience of courses (good example: goo.gl/KB6XA4)

- Interviews of professors teaching the courses

- …or anything else that seems promising and convincing!

In general, reviews stretching across a large number of universities tend to take on a somewhat less detailed approach to the content of the courses and mainly look at course titles and perhaps also course descriptions, which most often are openly accessible through the university’s website. However, if you are only reviewing one university economics degree and are students or staff at the university yourselves, you probably both have more time and more access to resources and people to make your review a bit more detailed. Some sources, such as exams, essay questions and coursework will of course require that you have contacts who can supply you with these from the university internally. These logistics are things you need to think about.

Surveys can also be really helpful. A smart move is to have some more “open” questions to allow for the more qualitative perspectives, and make a number of more “systematic” and multiple choice questions of which you can easily quantify. In the Durham report, for example, they also conducted a survey and tried to let each question represent each of the aspects they wanted to investigate in the curriculum review. In this way, not only could they see whether they were represented physically in course descriptions and exams, but also how much their presence was felt or appreciated by students. For survey questions and results, see goo.gl/jfA1qx. Google forms can be useful here as a data gathering tool. Remember to choose your questions carefully and always have a purpose with each question. The longer the survey, the smaller chance there is that people will complete it with thought.

Opinions from lecturers might also be useful. Ask them what they want the students to get out of the course or perhaps see if they agree with you on that 80% of the questions in their exam doesn’t encourage any evaluative or critical thinking. This wouldn’t necessarily reflect the actual content, but would reflect on whether the results of your research reflects the professors aim with the course, or if it might be exam questions or course content just haven’t been designed properly in line with what professors expect out of their students.

In general, the choice of data also depends on your audience. Keep this in mind when you make your choice: who are you trying to convince, and what kind of data convinces them? If your primary audience is the general public, or policymakers, then you might well want to choose something more ‘human’ than statistics. But if your primary audience consists of economists, numbers work well.

Choosing review criteria

Some decide to do a completely neutral review and only sum up what modules are offered in each degree, which the French, the German and the ISIPE research has done. This is a great approach if you want to cover a lot of bases quickly, or do an international comparison. It is relatively easy and won’t be attacked, because there is almost no possible controversy in interpreting your results. After all, you simply followed the course names as they were given and did a simply addition exercise. Yet it can still show very powerful results. If you choose this approach, make sure that the same course name means roughly the same course content throughout your research area. I.e. “micro-economics 1” in Kassel = “micro-economics 1” in Paris?

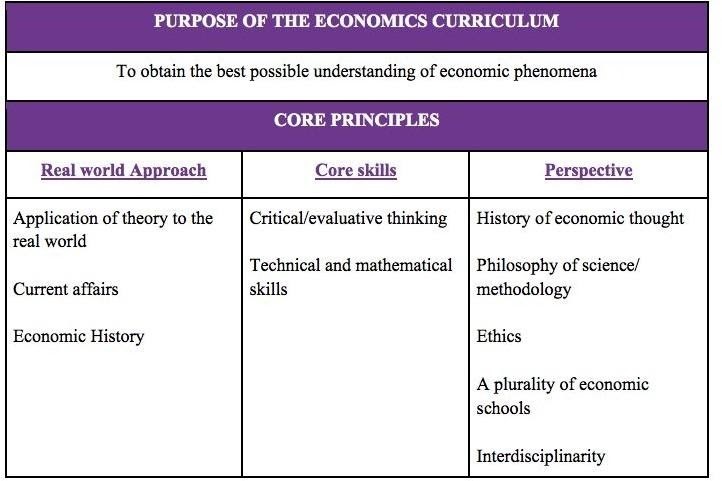

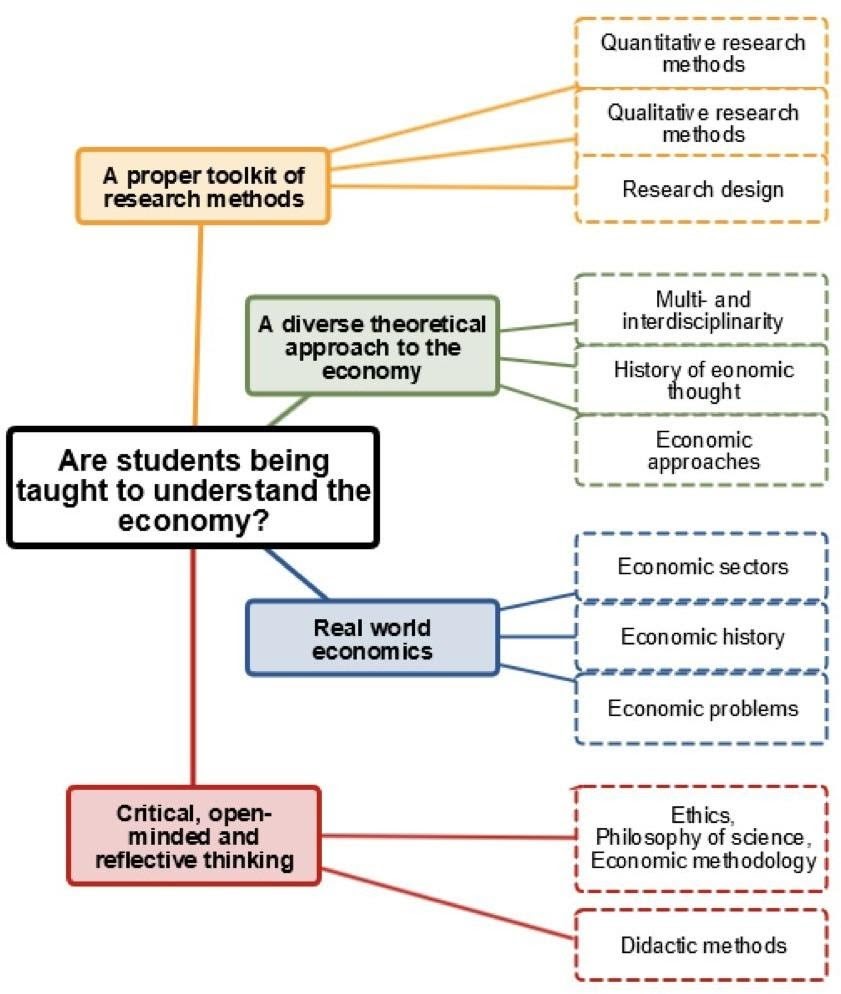

On the other hand, other reports decided to take on a more normative approach and at the start ask themselves What should an economics and/or business degree teach their students?. The purpose of the review is then to investigate to what extent the curriculum is living up to these criteria. This was done in the Netherlands report, the Econocracy and Durham’s report. Asking the above question and narrowing down what criteria to look at can nevertheless be very difficult as it inevitably will lead you on to other even broader questions, one which will lead to another. These are some of them.

- What is the purpose of economics/business as discipline?

- What needs to be included in an economics/business degree for this purpose to be achieved?

- On the other hand, What is the purpose of an economics/business degree? (Is it actually there to achieve the purpose of economics/business or does it have some other instrumental value for society?)

- In this light you might want to ask, What do most economics/business students go on to do after they graduate? What skills and knowledge are sought after in their jobs?

- You might even end up asking What is the purpose of a university degree?

Two examples (Durham and Netherlands):

The theoretical framework you decide on you can then break down to certain criteria and/or categories which you can investigate more systematically. For example, in the Econocracy they have categorized all the exam questions in the following four categories: (1) Operate a model; (2) Describe questions; (3) Evaluate questions; and (4) Multiple choice. In doing so they showed whether students are being asked to have technical modelling skills, reproduce knowledge, use their independent judgement or just fill in the right option.

4. Writing the report

General considerations

Time

One of the most important steps in writing a report is coincidentally the first: starting. Starting early in the academic year, or perhaps in the summer beforehand, gives you the most time to prepare, receive feedback, and revise. Even if you write the report quickly you’ll want to get input from people who have their own busy schedule and perhaps can’t get back to you immediately, budgeting some extra time will save you a headache. In the process of revising some sections may need to rewritten or perhaps added entirely, limiting your time further. For students, time is already a painfully scarce resource, so giving yourself some leeway by starting early will improve both the report and your

levels of stress. A good way to keep on track is to set up smaller individual deadlines throughout the year so that you can monitor progress and results.

Having said this there’s one caveat worth adding. When a deadline seems far in the future it can be easy to procrastinate and leave it to the last minute. How many papers have you had a term to write but left for the last 24 hours? (Maybe some of you are better students than that but spare a thought for those of us who aren’t) A good way to keep on track is to set up smaller individual deadlines throughout the year so that you can monitor progress and results.

Team

So hopefully you’ve decided to start early, what now? It’s time to build the team that will write the report. Who you decide to recruit and how to do it ultimately depends on the needs and circumstance of each society, but we will include some thoughts below.

- Consider avoiding recruiting too many people who already hold exec positions in your society. Writing a report can be a great way to bring in fresh faces and get them invested in pluralism. Writing a report is a big time commitment and members of the exec often have enough on their hands without piling on more work.

- Consider recruiting a curriculum officer who manages the project. Leadership and direction are absolutely essential to a project like this.

- For both of these points, however, it is important to make sure that people are involved or committed, and share a common vision. If not, see below.

- Have a plan for if someone on the team drops out. Whether it be time commitments, not having realized the work required, or some other miscellaneous reason it is useful to be prepared for losing a team member.

- Conversely as groups scale up it can be harder to manage and keep things consistent. Too many cooks will spoil the broth. Finding the right balance will be a difficult, but important task.

Once you’ve assembled a team you should answer a few guiding questions so that everyone can be on the same page about the review. In above sections you should have thought about determining your purpose, audience, strategy, methodology, tone, etc. This is where thinking about presentation or creating a style guide may prove useful. The contributors must be aware of the decisions you’ve made and adjust their writing accordingly. If the report comes across as inconsistent or unpolished, or have different tones and ways of writing, it can detract from persuasiveness.

Finally, having mapped out a timeline, plan, and tone for your report, be ready to spend a good deal of time on it. Finishing a report like this can be an incredibly rewarding undertaking, but it also takes a high level of time investment. Even if you finish early you’ll want to have plenty of time to review the report as well as getting input and feedback from lots of sources, and getting the publication strategy right. Lots of people will be happy to give you feedback, but only if you give them time to properly read through it given their schedule. Equally, remember that you don’t have to make everybody happy. This is your report, and feedback is yours to decide on.

Contents – what sections should you include?

There are many possible items you could include in a curriculum review, and the various groups cited in this guide have taken very different approaches. To save you an awful lot of headache, we created a brief overview of all the possible sections you could include, with pros and cons as well as examples for each of them.

Executive summary

This is always a good idea. It may be very obvious to you and me why this stuff is so important, and what it means that there is no History of Economic Thought or Sustainability course, but most outsiders do not understand what this might mean and the implications of its absence. So summarize it for them, and spend serious time on this: 90% of the readers of your report will only read this, make it count!

Example: p. p. 7-12 of Thinking like an Economist

Foreword

A foreword from an authority figure can help to have your report taken more seriously. Often, these forewords simply summarize the research and add a few words saying that it is very important stuff and everyone should know about it. Will also help with getting the report out through media. When students criticise what they’re being taught it can often lack gravity. If students had the knowledge to decide what they should be taught they wouldn’t be students is a common logic. By adding the authority of a respected author it can confirm the legitimacy of what you’re saying and overcome a bias against students.

Examples: Econocracy, p. xiii-xvii; Thinking like an Economist, p. 13-16; Educating Economists?, p 4-5

Introduction and rationale

Why should people care? Why is all this technical stuff important? Are you a few students who are dissatisfied about your own program, do you think all students of the program are ill-served, or do you feel that even the general public or society is done a disservice because of the way economists and business professionals are educated? Your story should start with that.

Write it from the outside-in. That means that you don’t start from the insider perspective of a student who knows their programme and knows what they want to get out of it, but rather from the further-out perspective of your readership. If you are writing for a general public, then start with a little story about the role of economists and business in society, or a brief history of the Rethinking and/or Oikos movement. The notion that it’s a socially important issue, or the notion that there are activist groups in over 30 countries pushing for the same thing, will help your readers feel the weight of the story.

Examples: p. 1-6 of Econocracy; p. 17-18 of Thinking like an Economist; Educating Economists p. 6-14.

Background and theory

Against what theoretical background are you writing this report, and how does that lead you to ask exactly these research questions? There is the longer historical perspective of how the economic discipline became narrower and rigidly focused on mathematics, or you can start immediately with the situation today. You don’t necessarily have to include this section, but it can certainly strengthen your argument. And even if you choose not to include it, make sure that you have thought about it.

It’s one thing to (briefly) describe the theoretical framework of your own research project, it’s quite another enterprise to go deeply into the philosophy of science and history of economics as a discipline. The authors of the Econocracy chose to do this, because they wanted to show not only what was wrong with their education, but also to explain the background, the way the discipline has evolved over the past century and the direction where it’s heading now. So they spent a full chapter on this.

The Dutch report takes a similar approach, spending some 15 pages on explaining the different ways ‘economics’ has been conceived of over the centuries. We found this to be necessary, to support our theoretical framework, which showcases a sort of dichotomy: we claim that you shouldn’t be learning to ‘think like an economist’ primarily; economics should be about understanding the economy. Today, this is not common sense in economics faculties. Most academic economists think of the discipline as a bundle of methods, a way of thinking. So we wrote a section showing how this has changed since Adam Smith, and how for most of this period, thinking about the economy was what economists did.

Examples: The Econocracy, p. 34-40 for the theoretical background and p. 92-121 for the perspective on the economic science and its recent history; Thinking like an Economist, p. 19-44; Educating Economists, p 8-18

Methodology & Discussion

You need to add some methodology, but it’s generally fairly boring work, and will only be read by (a) those who want to do similar work (b) those who are looking for something to attack you on. So the extensiveness of this section mainly depends on how many attacks on your data you expect. You can choose to put this in an appendix, if you don’t want to break the flow of your story with methodological humdrum. Can contain an explanation of the data used, how you got that data, how you weighed different variables, how you categorized courses, etc.

A discussion section is also something to consider, for two reasons. First, it looks more academic if you admit the limitations of your research (and sticking them in a discussion section means you can go all-out in your conclusion and summary). Second, a discussion can help others wanting to do similar research or wanting to build on what you have done. However, a Discussion section is by no means a necessity.

Examples: The Econocracy, p. 185-192 (in appendix); Thinking like an Economist, p. 57-72, Educating Economists, p 15-18

Results

Obviously, you need to describe your findings. There are different ways to do this. You can do an academic paper-style format, giving dry statistical results, and leave the interpretation to the Conclusion section. Thinking like an Economist did this, in order to be taken very seriously as an academic-standard publication. Or you can directly integrate it with a normative narrative, on the consequences for society when economists and business professionals have side-blinders, as the Econocracy did. There might results that you like, and there might be results you don’t like.

Although emphasising the results that is supporting you case is important, one should always also include the result the results that opposes your argument. First and foremost, this is important because this the right academic approach. Moreover, it makes the report and you as an organisation appear more trustworthy. Rather than neglecting the results, one should discuss them properly and

give plausibel reasons for why you got this result. For example, a student survey might show that most students don’t think there is a lack of perspectives in the curriculum. Could this be because they don’t know about any?

Examples: The Econocracy, p. 40-57; Thinking like an Economist, p. 73-86, Educating Economists, p 18-26

Social consequences of the current curriculum

Many of us started studying economics and business to understand the central driving mechanisms of society, and did not find much in their courses to develop this understanding. What consequences does it have for society if we have narrowly educated economists and business professionals?

This is also not a necessary section, and the target audience of your report should determine whether you include it. It might be more relevant if you write a country wide report. On the one hand, if your report should be very dry and factual (strategic, in some situations) and you feel that your audience will mostly be offended by your inclusion of such a section, then leave it out. On the other hand, if your audience is the general public or political decision makers, they should feel very clearly why this is not just a matter of dissatisfied students, but society as a whole is being short-changed. In that case, make this section bigger and more central.

Examples: Econocracy, p. 34-59; Thinking like an Economist, p. 95-96

(Policy) recommendations

When considering suggestions for change, it is important to go back to your strategy and consider the suggestions in light of this. If some suggestions might be too radical and can take too much attention, other important suggestions get neglected. However, in some situations it might be useful to present radical ideas. If you suggest such ideas, you might get a no, but it can then be easier to win through with other suggestions.

It might be smart to include some paragraphs on what obstacles to change there are at your university. This highlights what would be necessary long term changes and shows to you counterparts that you are aware of difficult constraints such as a limited timetable. For example, considering long term changes, in UK the Research Excellence Framework, the guideline for national academic studies, incentives research in mainstream economics which makes it hard for universities to recruit academics focusing on other schools of thought. Changing this would be an important long term project and deserves to be highlighted.

A last advice on this is to make the suggestions concrete and take the current state of the situation into account. Rather than saying “We want the curriculum to be more pluralist”, make suggestions on modules to include. It is also important to suggest something which has taken the situation of the faculty into account. Then you might suggest to include a module on “Post-Keynesian Theory” because you know that you have this capacity at your faculty. Being both concrete and have taken the situation into account makes it harder for people to attack you and more likely for you to make a change.

Examples: Econocracy, p. 122-149; Thinking like an Economist, p. 97-99, Educating Economists, p 27-48

Inspiration for a better curriculum

It is also possible to add material to the report which you would like to see added to the curriculum. Of course, there are many sources for such material. A few of these include:

- Economy Studies: A New Approach to Economics Education (book on how to reform economics education full with practical tools and teaching material) www.economystudies.com

- Business Building Blocks

- Rethinking Economics: an introduction to pluralist economics (textbook with introductory chapters on 8 different schools)

- www.exploringeconomics.org/en A website with similar material, and a lot of MOOCs.

- https://www.economicseducation.org/expand-your-thinking/ A website with an overview of pluralist and heterodox textbooks, BSc and MSc programs and other materials.

- https://www.core-econ.org A curriculum designed by an INET working group, which is a step in the direction of being more real world connected.

- http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/ A website with material on the History of Economic thought and different economic schools

Conclusion

This is where you can step away from the boring jargon again and make it very clear what you mean. And the good thing is: most non-technical readers will only read your conclusion, not your methodology and often not even the results section. So make it snappy, and spend time on polishing it. In a serious report, the conclusion is one of the few places where you can really put in a strong opinion, or at least put a strong framing on your findings (not just: “80% of courses focus on maths, 20% focus on…” but “there is an overwhelming focus on maths, to the detriment of other ways of seeing the world”).

However, you don’t need to have a conclusion section, especially not if your report is normative throughout. It is generally something readers like, as it means they don’t have to read the rest of the report. If your report is short enough for them to read as a whole, it is worthwhile considering to leave out the Conclusion section, so that they’ll have to read the whole thing instead. Alternatively, if you are writing in a more free-flowing format like the Econocracy authors, there is no need for a Research Question – Methods – Results – Conclusion structure.

Examples: Thinking like an Economist, p. 91-94; Educating Economists, p 47-48

Appendices

Remember, you can always put the really boring stuff in appendices. If your are printing your report and distributing it in physical form, a suggestion is to include just a link in the report where people can access the appendix online – save the paper for the planet.

5. Publishing and getting attention

So, you wrote a curriculum review. Great! That is an impressive piece of work. However, now comes step 2, which is at least as important: get your work out into the world. This is highly related to your strategy, so it is important that you plan all this in the light it. Most people, including most likely allies, will not take the time to read your entire report. This is annoying but it’s also reality. However, you can still reach them. This section explains some ways to bring your findings to the daylight, like they deserve.

Make accessible material

Select a few central data points / quotes

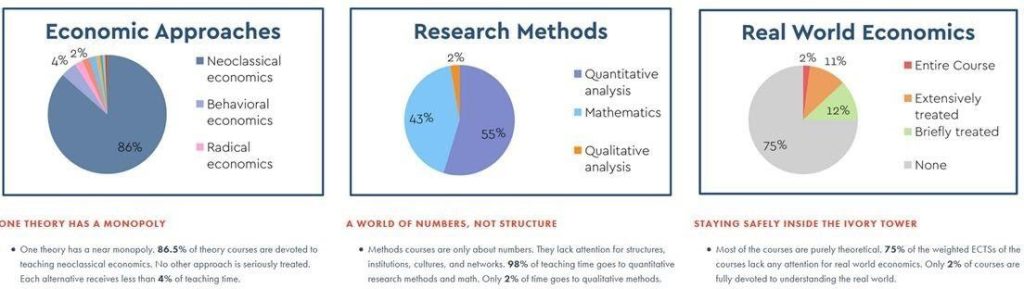

A thorough curriculum review is a great thing, but it can also be very powerful to simply select 2-4 central data points and/or a few strong quotes from students (if need be, just quote yourselves). This should be a small, small selection from your results. An example from Thinking like an economist:

These core points ended up in almost every medium where the report were discussed. If there’s only your entire report, an outsider, reporter, faculty member or fellow student may not know where to start when talking about the report. But these statistics, coupled with the one-liner descriptions below, allowed people to immediately start the discussion. You can also put them on stickers, or flyers, to be handed out at lectures or to put into faculty’s mailboxes.

How to write a catchy summary

In this summary, start with the conclusion, the core findings. It sounds counter-intuitive, but it’s the best way to capture the attention of your reader. Then, you explain how you reached that conclusion. Ideally, write two: a long one, of several pages, to put in the report, and a short one, of a single paragraph, to include in e-mails and in a press release (if you do one).

Make it visual

“Economics starts with a pencil – visualize!”

Kate Raworth

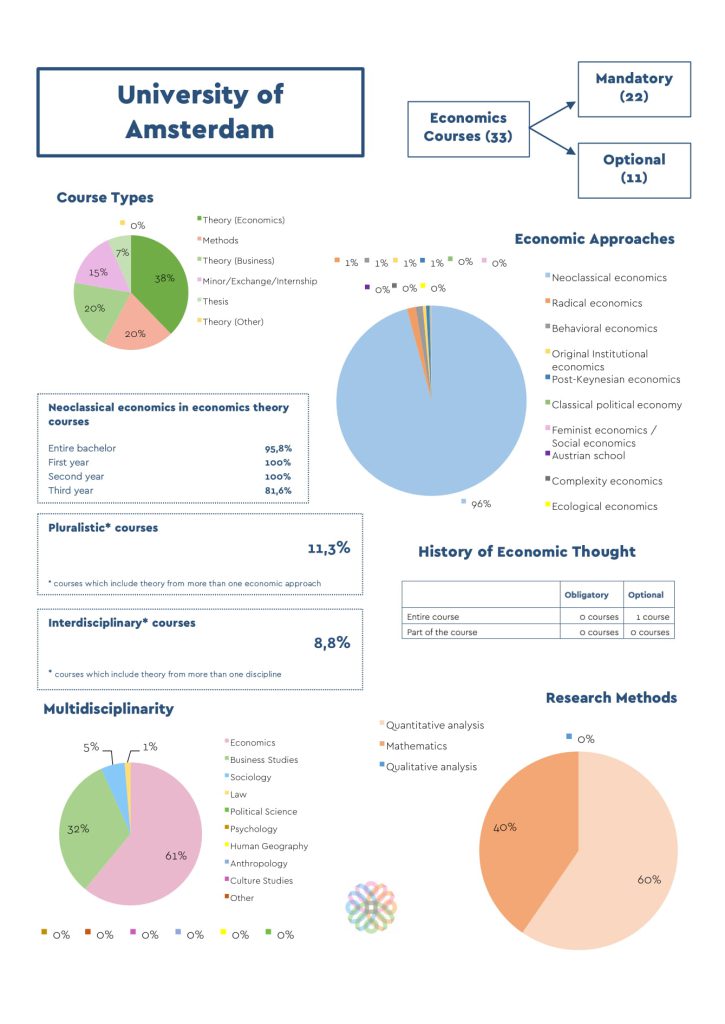

A visual overview can really help to make your results quickly and easily accessible, and can help to put on the table during talks with faculty or outsiders. For Thinking like an Economist, we made a fixed format of graphs and charts, which we filled out with the relevant data for every university. See below for an example, from Thinking like an Economist, p. 116-137.

Organize media attention

Create a Press Release

A press release is a 1-2 page document (not longer!) that you send to journalists, big and small, hoping that they will write about your work. It’s best to call the various media first, explain your situation and ask whether they’d be interested in a press release. Then send it out. Of course you can send it without calling them, but this way you have a bigger chance of them actually reading it.

What should go into a press release? Here, try to think from the journalist’s point of view. It’s easiest to think of journalists as very lazy people, and write your press release accordingly (of course, most are not lazy, they’re just very busy). Give your press release a headline which you’d like to see in the newspaper/website/…, so they don’t have to imagine it themselves. Set out in a single paragraph what the story could be, for the same reason. And be sure to include a few ready-made quotes from students. Journalists often put these into their articles, as if they have really interviewed the students, and it makes it much easier for them to write the article. Also good to add: comments from professors and other authority figures on the report (which you ask them for). Same trick: the journalist puts it in and gets a good piece without having to make a lot of phone calls.

Examples of press releases are in the databank (see p. 1). For more advice on how to craft a press release, contact the Rethinking Economics organisers at press@rethinkeconomics.org.

Do an opinion piece (op-ed)

Opinion pieces are often based on longer work like a report or a book. This works easily, because you already have your material and your data, and in all likelihood you also already have your opinion. So it’s just a matter of putting those together and getting them into your university newspaper, economics section of a regional or national newspaper, or on online platforms. Where to publish this? In fact, anywhere goes. Just e-mail the editors of any print, online or other medium explaining that you are economics and business students who are protesting the nonsense that you’re being taught, and they are quite likely to be interested. Student protests are an established ‘news format’, which really helps to get your piece through to the editors. Here is a good example of such an op-ed: goo.gl/rQ3hcx.

Rank various programs against each other

One final media trick to garner attention is to rank various programs against each other. It’s a risky enterprise, and you can be very sure to draw the ire of those on the bottom of your ranking. This is largely a ‘bad cop’ strategy. But if you are not being listened to by the faculty, then a ranking is probably the shortest route to get a lot of attention. Everybody wants to be #1, it’s a basic human tendency.

And of course, you are ranking the various programs on benchmarks of your choice – not by student numbers or mainstream publications, but by pluralism, sustainability, diversity, amount of real world relevancy and so on. For examples on how to do that, check out the NGO Rank-A-Brand (rankabrand.org), which has perfected this technique – it’s all they do!

Online platforms

If your group has a Facebook page, that’s a good place to spread the word. The same goes for Twitter, any membership mails you might regularly send out and other social media channels you have. But of course, others are also sending out newsletters and are looking for content. You can plug your report in there. Perhaps the department or university has a student union or similar organization, which would also have good communication channels. If you conducted a survey and collected emails, let participants opt in to receive the results when the report is finished.

Alternatively, you could create a blog or website and put the main findings or indeed the entire report on there. The Dutch guys went kind of overboard on this, creating an entirely new website www.economicseducation.org. If you already maintain a website, this becomes much easier.

Events

Easy events

The simplest event you could do is simply to stand outside a lecture hall and hand out flyers, or (ask for permission to?) give a brief talk at the start of a lecture. You can also ask sympathetic professors to do so on your behalf. If you have more time and energy to spare, it can be very effective to engage with the faculty more directly. Ask for permission to give a brief presentation at a faculty staff meeting about your results. This is the surest way to get everyone’s attention, quickly. Another crude, but very effective technique is to simply show up at the staff rooms with a big box of your reports, walk around and hand them out to everyone. If your report covers various universities, you can make this into a roadtrip!

A big splash

If you want to bring people together and engender more of a movement vibe, organize a public launch party for your report. This can include lectures, workshops, games, documentary screening or whatever else seems like a good way to attract people and get the message out. You could even invite journalists to this, whether from national media or from the university or department (online) magazine. The Econocracy writers managed to get the Bank of England Chief Economist to speak at their press launch event, while the group from the Netherlands went the popular route and organized a Rethinking Festival (including a Keynes vs. Hayek rap battle and a barbeque). Anything goes!

Attention, attention, attention!

Promotion is the only way that your report will gain traction. It is important to be as dedicated to communicating your findings as you were to creating them. You’ve invested a large amount of time in the report, don’t let it go to waste!

6. Evaluation stage, getting feedback and long-term change

A good thing to do when your massive launch is over, students and academics have had time to react to your report and you have recuperated from your post-traumatic stress, a good way to keep the discussion going is by trying to gather feedback on your findings. Set up meetings with the staff of your Economics and Business department, email your professors and interview students – ask what they thought about your theoretical background, about your findings and about the suggestions you might have made. It is important to know the reasons to why some might not agree with you, only then are you able to understand how to make your arguments stronger. You might also have made mistakes or things which you might not have thought about (this guide is of course to try to make you avoid this).

These insights are essential for how you will continue the discussion now, but also for coming students, academics and activists who might make another report on they same curriculum(s) in a couple of years and who can learn from your successes and mistakes. Also, curriculum change probably will take at least a couple of years to achieve at a university, and these changes may be small. It is all about keeping the debate going. Students come and go, but it is important that all your work doesn’t get forgotten.

Conclusion

This is not a conclusion. We just want to say: happy to see that you made it to the end of this document, even happier that you have decided to be part of the Rethinking and Oikos movement, and even happier that you apparently share our passion for doing this kind of research! We know how hard it can be, so we wish you all the best with the project. We’d be very happy to hear from you, whether your research is progressing fast, slow, easy, or not at all as planned – neither did ours.

This handout emphasised some of the struggles and difficulties of writing a report. While it is important to be honest about these things, we don’t want to give the impression that writing a report is all pain for no gain. Not only does it bring huge benefits to your cause, but it will help you better understand both your degree and the cause we all care about. While writing a report is a substantial time commitment, those of us who have gone through the experience would agree it is undoubtedly worth it.

We also hope that this document will continue to develop. New curriculum reviews will be written, bringing in a lot of new experiences. Some of you might got some good ideas and suggestions just based on reading this. Anyhow, we hope that you will give us any feedback you might have!

If you want, we can also Skype/e-mail about this stuff. It’s impossible to put everything in such a document that would be relevant for your particular situation, and in fact, conversations often bring out topics in new ways. Feel free to contact us, even if you don’t have specific questions but would just like to discuss doing this kind of work in general.