Companion to Building Block 7: Research Methods & Philosophy of Science

In this resources chapter we go into more detail into what research methods and philosophy of science can be taught in economics programs. The related building block, Research Methods & Philosophy of Science, briefly sets out the elements which we believe should be at the core of teaching this topic. In this chapter, we elaborate on what can be taught when there is more space and teaching time available. We start the chapter by discussing the main issues surrounding the teaching of philosophy of science. Second, we give a short overview of relevant research methods, ordered by two axes: qualitative and quantitative; data collection and data analysis. Finally, we discuss how qualitative and quantitative methods can be combined in mixed methods research designs to complement and strengthen each other.

Philosophy of Science

Here we briefly discuss different underlying philosophies of looking at the world and contrasting ways of studying the economy. The main purpose is to give a short indication of the type of issues that are valuable to impart on students when teaching philosophy of science. First, we delve into the various aspects of epistemology and how knowledge should be generated. Second, we discuss ontological issues relating to the nature of the economic world.

Epistemology refers to the study of knowledge, centred on the question: how can we know things? We suggest teaching the following four strands of epistemology: positivism, interpretivism, (critical) realism, and pragmatism. Positivism assumes that reality can be directly observed and objective facts can thus be discovered. Interpretivism opposes this by arguing that reality always has to be interpreted and knowledge is therefore created through perception and experience. Critical realism places itself in the middle of these two positions by arguing that reality can be observed, although never in a direct manner. Finally, pragmatism changes the focus of the debate by arguing ideas should be judged by their practical usefulness.

Besides these different ways of thinking about objectivity and the value of knowledge, there are also contrasting ideas about how research should be done. Broadly speaking there are three methods of reasoning: deductive, inductive and abductive. Deductive reasoning uses logic to arrive at conclusions that are necessarily true given a certain set of assumptions. Inductive reasoning moves from the particular to the general and in doing so arrives at probable conclusions based on empirical evidence. Abductive reasoning is often described as searching for the most likely explanation for a set of observations. Specific methods are often more strongly related to one of these modes of reasoning than the others. Among qualitative data analysis methods, content analysis is, for example, associated deduction and grounded theory with induction. These links are, however, often more relative, as many methods have, for example, both elements of deduction and induction in them.

Ontology, then, refers to the study of being and the nature of the world. The central question is: what is? whether the subject of study is people, societies or economies. An important divide in this regard is between scholars who are convinced there is an objective world out there, often called objectivists, and those who believe reality is constructed by social actors, including the researchers themselves, often called constructivists.

Another aspect of ontology is whether one sees the world through the lens of methodological individualism, holism or relationalism. Methodological individualism assumes that all phenomena can be reduced to individual characteristics (such as preferences) and acts (such as buying a product). Methodological holism, however, argues that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts because of emergent properties, properties which arise at a system level and do not belong to any individual part. Methodological relationalism understands the social world as being made up of social relations and interactions.

Furthermore, students should acquire a basic understanding of the differences between the social and natural sciences. For one, social scientists are part of the social world they study. That means their ideas (can) influence and change that world, sometimes called performativity, whereas the workings of the natural world are generally unaffected by the ideas of natural scientists. Another difference is that it is (practically) impossible to fully control the social world in order to conduct scientific experiments. Social scientists have to make do with quasi-experiments, natural experiments and other sources of data. A third important difference is that the natural sciences can arguably assume universality of laws, whereas social scientists have to work with more degrees of variability and historicity of specific economies, societies, cultures and even individuals. Therefore, it is important to spend some time on these distinctions between the social and the natural sciences. Especially because economics is a social science in which numbers play such a big role, which has sometimes led to confusing it for a natural science.

To conclude, epistemology and ontology are related to each other, although in a complex way. For example, while both positivists and critical realists are convinced there is an objective world out there, they differ on whether that world can be directly known (positivists) or not (critical realists). More importantly, these different methodological approaches should not be seen as binary options, but instead as varying degrees. A study is thus not either fully positivist or interpretivist, but in each small methodological choice involved in the research a more positivist or interpretivist option is chosen, thus resulting in the fact that almost all studies are partially positivist and partially interpretivist. Teaching students methodology is therefore not a matter of finding the true methodology, but instead it is about knowing the various options and their implications, in order to be able to understand other research(ers) and make informed decisions in specific situations.

Research Methods

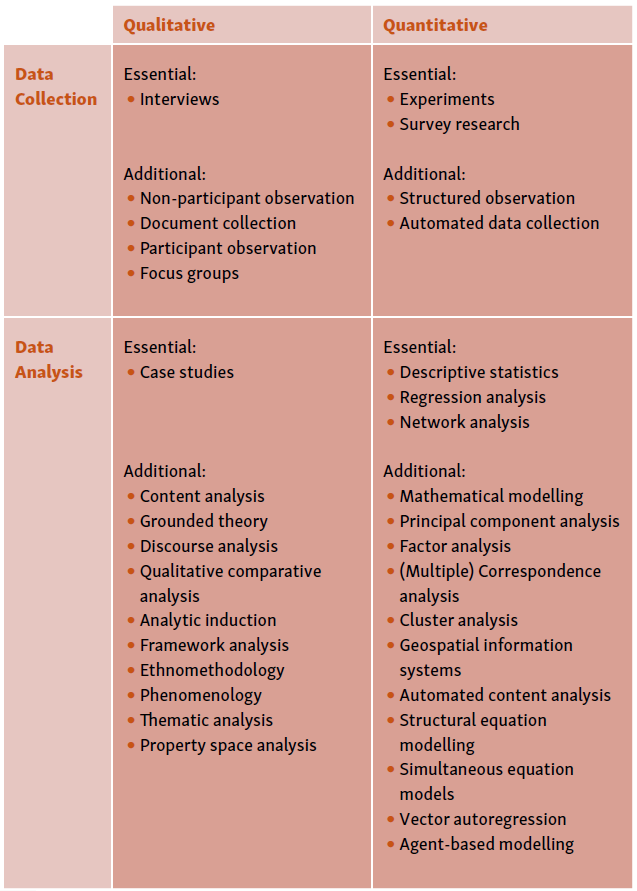

In the building block, we focused on the research methods we deem most important and essential to teach to economics students. There are, however, many other relevant research methods that can help gain valuable insights into economies, and many of these are crucial if students decide to specialize in a certain field. If a student, for example, decides to specialize in qualitative research methods, it is key that he or she also learns about doing observations and how to apply content analysis and grounded theory to qualitatively analysing data. On the other hand, a student focused on quantitative methods would, for example, be helped by learning about factor analysis and agent-based modelling. As such, there are many relevant methods that are perhaps a bit too much to teach to every economics student, but are important for those specializing in a certain direction.

According to this logic, we put methods in two categories: essential and additional. We are very aware that this categorization is likely to be contested and we advise teachers to change them according to their own views. But we do advise to keep the list of essential methods limited, in order to keep it practically feasible to teach in a program.

In the table below, we present an (incomplete) overview of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods. This is meant to illustrate the wide variety of options there are when teaching research methods to economics students. A further extension and improvement of the list would be very welcome.

Qualitative data collection

As explained in @BB7, we think it is crucial for economics students to gain a basis in doing interviews as they will likely use this technique later on in their careers, for both academic and non-academic purposes. Interviewing is, however, not the only relevant qualitative data collection method. If there is room in a program for students to further learn about and specialize in qualitative research methods, we would advise to also teach document collection, observation and focus groups.

Document collection is often used by economic historians and is also very useful when conducting case studies. Focus groups are particularly useful as they allow researchers to observe how people interact with each other. They are not only used for academic purposes, but are also highly popular in marketing as well as political research. Observations, on the other hand, are particularly helpful for analysing ongoing economic processes and for gaining first-hand experience with them. Observations can be done both with and without actively participating in them, each research method with its own advantages and disadvantages. Participant observation, often used by economic anthropologists, can, for example, help gaining what is often called tacit knowledge which is not easily communicated but nevertheless crucial to how economies function.

Quantitative data collection

For quantitative data collection, there are also more options than we discussed in @BB7. A particularly promising method seems to be automated data collection. With the help of software, it is possible to automatically identify and extract data. This allows researchers to collect larger amounts of data than previously possible and it is therefore often referred to as ‘big data’. A recent application of this method to economics is The Billion Prices Project of MIT professors Alberto Cavallo and Roberto Rigobon in which they collect prices from hundreds of online retailers around the world to be able to create daily, rather than quarterly, price indexes. Many social sciences are increasingly making use of these new data collection methods, it is crucial that economics does not miss out on these recent developments.

Qualitative data analysis

Now we turn to data analysis methods. In @BB7, we emphasized that it is important for students to learn how to do case studies. To systematically analyse qualitative data, such as texts from interviews, there are many tools and techniques as well as software students can learn to work with. These methods range from well-known approaches such as content analysis and grounded theory to lesser known approaches, such as qualitative comparative analysis and analytic induction. As stressed in @BB7, we think it is key that students become aware of the different methodological choices they can make and learn to critically reflect upon them. So rather than training students to become fully specialized in one of these approaches to analysing texts, we advise to teach them a broad range of methods so that they can be applied pragmatically based on the topic at hand.

Quantitative data analysis

Finally, quantitative data analysis, the core of current methods courses in economics programs. As explained in @BB7, we think that current teaching can be expanded by including network analysis, next to descriptive statistics and regression analysis in core methods courses. For those students aiming to specialize in quantitative data analysis methods, we advise to learn about mathematical modelling, but also become familiar with promising and increasingly used methods, such as agent-based modelling. Furthermore, there are some highly useful methods which are regularly used by other social scientists, but not that often by economists, such as (multiple) correspondence analysis, geospatial information systems, automated content analysis and structural equation modelling. These methods do not only provide opportunities for innovative academic research, but also provide important opportunities for practical applications for both policy and commercial purposes.

Mixed methods research

These individual research methods can also be combined in research projects to allow them to strengthen and complement each other. Such combinations can be between multiple quantitative or qualitative methods, also known as multi-method research, but combinations can also mix qualitative and quantitative methods. When qualitative and quantitative research methods are used together, it is called mixed-methods research.

While purely quantitative research is still dominant in economics, an increasing number of economists is conducting innovative research using also qualitative research methods in mixed methods studies. An example of such a study is the field experiment supplemented by interviews by Turney, Clampet-Lundquist, Edin, Kling, & Duncan in their 2006 study Neighborhood effects on barriers to employment: results from a randomized housing mobility experiment in Baltimore. To better understand what happens to lower-income people who move into better-off neighbourhoods, they conducted a randomized control trial with 636 participants in Baltimore, analysed using regression analysis, and in-depth interviews with 124 people from a stratified random sample, analysed by using analytic induction. By doing so, they found that the isolation from networks of information about job opportunities for low-skills workers offset advantages of living in better-off areas.

Read more about mixed methods studies in economics:

- Qualitative and mixed‐methods research in economics: surprising growth, promising future by Starr, from 2014.

- Mixed-methods research: What’s in it for economists? by Jefferson, Austen, Sharp, Ong, Lewin, & Adams, from 2014.

- Multiple and mixed methods research for economics by Cronin in the Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Heterodox Economics, from 2016.

- Qualitative and mixed research methods in economics: the added value when using qualitative research methods by Jemna, from 2016.

- An introduction to mixed methods research in agricultural economics: The example of farm investment in Ontario’s Greenbelt, Canada by Akimowicz, Vyn, Cummings, & Landman, from 2018.

- Mixed-method approaches to strengthen economic evaluations in implementation research by Dopp, Mundey, Beasley, Silovsky, & Eisenberg, from 2019.

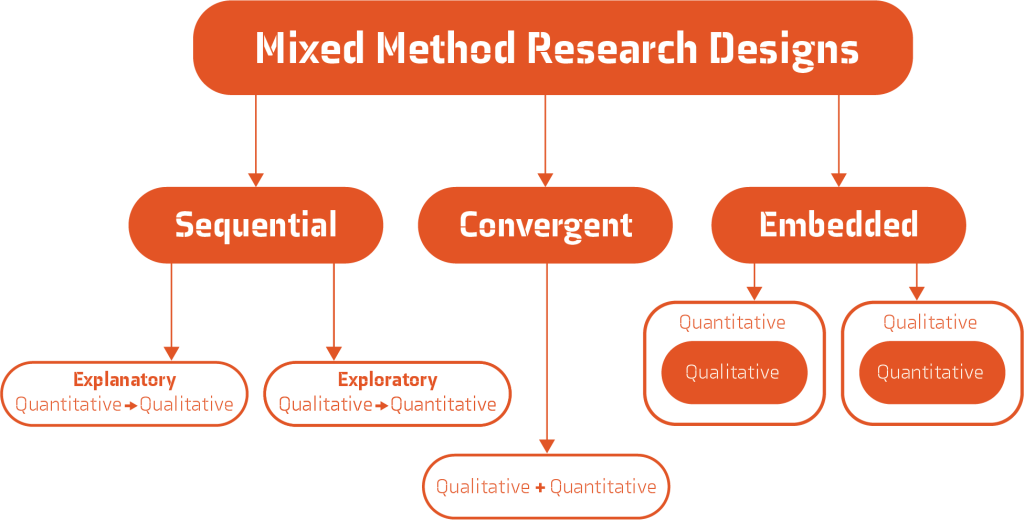

There are a number of different ways in which qualitative and quantitative methods can be combined in studies. Below we shortly describe the main research designs in the literature (see the figure below).

First, there are two sequential research designs in which one set of methods is followed by another set of methods in the study. If the qualitative research precedes the quantitative research, it is generally called an exploratory design. This is because it starts with an open-ended qualitative phase followed by a quantitative assessment and in doing so allows researchers to explore new issues and themes. The exploratory design is often used to develop new measurement instruments, test and generalize qualitative findings in a quantitative manner. The other sequential research design is explanatory as it starts with quantitative research and subsequently used qualitative research to further explain and contextualize the findings. Based on the quantitative results, interesting cases, which can be outliers, typical, contrasting, or random cases, are selected to be further investigated qualitatively.

Secondly, there are concurrent, or convergent, research designs in which qualitative and quantitative methods are applied in parallel to each other. Often this design is used to triangulate or complement findings. By analysing a topic both qualitatively and quantitatively at the same time, researchers can compare whether the different methods come to the same conclusions or whether they bring out different things.

Thirdly, there are the embedded, or nested, research designs, which can be concurrent or sequential. In embedded designs, there is one dominant method in which another method is embedded to support the dominant method. In this way, a deeper and broader understanding of the topic can arise and the weaknesses of the dominant method can be offset. A prominent way of doing this is, for example, to have as dominant method a quantitative experiment and have as supportive method interviews. In doing so, the interviews can help by providing more detailed, open-ended and rich information about the processes that happen during an experiment.